House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home

The Philosophy of Collage as Influenced by Marxist Theory

Freely repurposing images in service of communicating a message reflects the overall democratization of art. Marxist philosophy is arguably the single greatest influence on the state of the contemporary art world, and has affected virtually every aspect of its community and production, which manifests significantly in the use of collage. Collage is a medium that encourages the viewer to think critically in seeing connections between seemingly dissimilar subjects, requires materials that are accessible to most all economic classes (in contrast to media historically associated with fine arts), and doesn’t necessarily require formal training or education to engage with. Picasso is often credited with the creation of art history’s first collage, a mixed media still life which introduced questions about the relationship between the “real” and “artificial”, the content of which Budd Hopkins emphasizes in Modernism and the Collage Aesthetic primarily “concerns collage not as a physical technique, a marriage of contrasting materials, but rather as a philosophical attitude”1

Collage is antifascist. Collage is engaging with the pieces of your world, tearing it apart, and reshaping it on your terms.

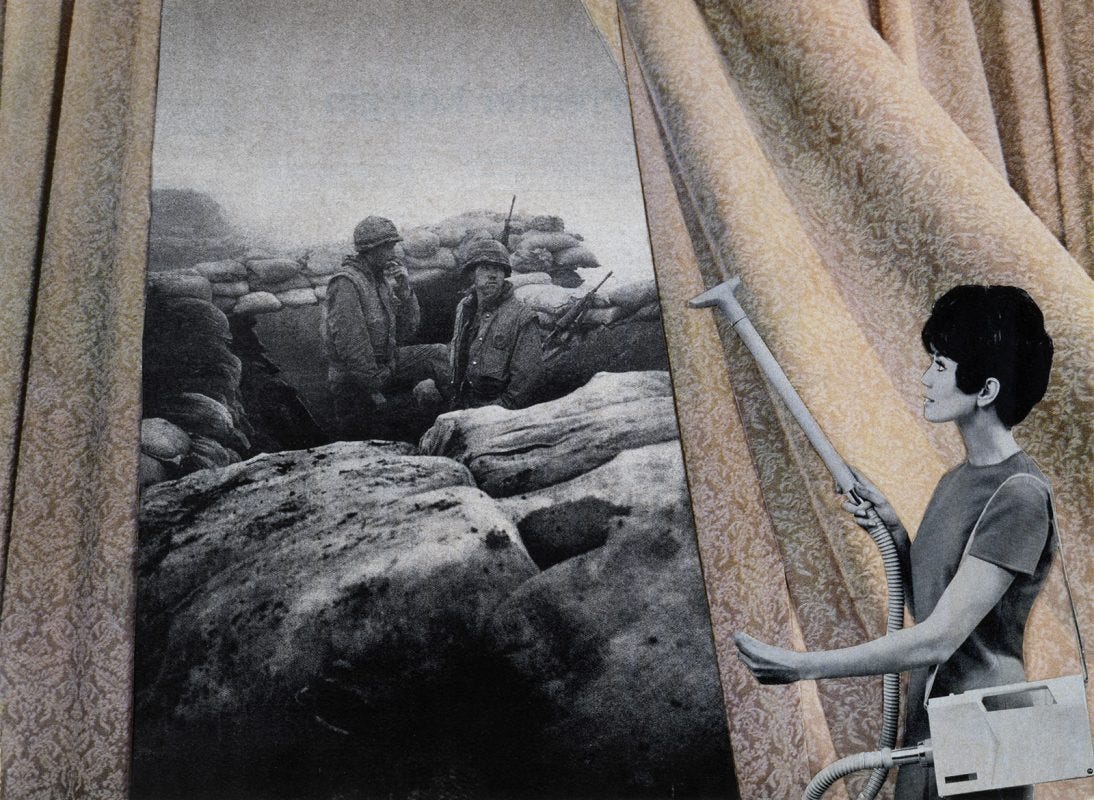

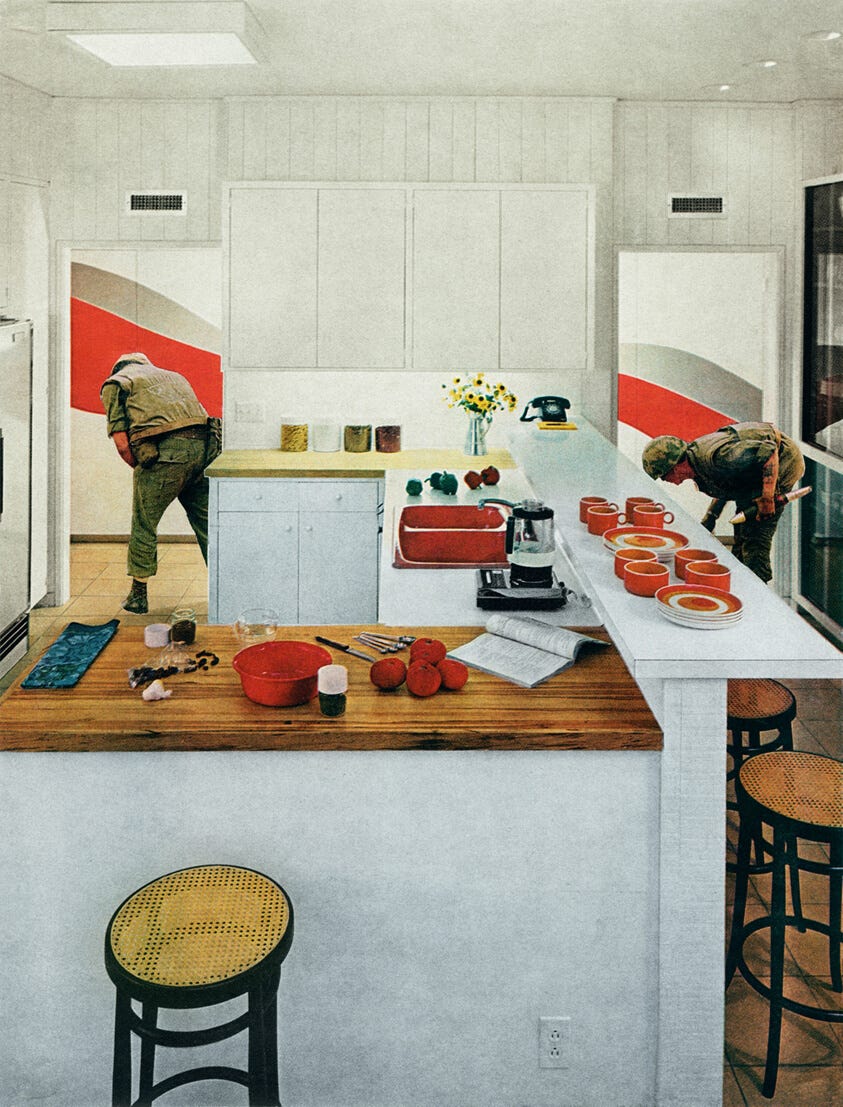

In her series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967-1972), Martha Rosler utilized collage to splice together images of violence from the Vietnam War (published in Life magazine) with images of affluent American homes featured in House Beautiful magazine. Recombining photographs with such a stark contrast in tone attached an atmosphere of absurdity and sardonic humor to the realism of the images. The series is a collection of twelve individual collage pieces, composed of cut-and-pasted paper on board. Their size fluctuated since, rather than being displayed in exhibitions, they were often printed in underground publications or distributed as flyers at protests. Rather than focusing on more traditionally celebrated technical skills/execution, the emphasis here is placed on the concept of the piece, and the complex relationship that it illuminates between the military industrial complex, consumerism, and the concerns of second wave feminism.

As a primary focus of the series, the Vietnam War was a conflict which stemmed from opposition from the US toward the mounting global influence of Marxism. In reaction to support provided by the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China to revolutionary efforts in North Vietnam (sparked by Ho Chi Minh, a member of the working class, who brought Communist ideology to Vietnam following his time traveling to numerous other countries) American military forces intervened.2

This work confronted the psychological dissonance of many Americans regarding the contrast between domestic life in the US and the violence enacted on the Vietnamese population by the US military, in addition to exploring the way the performance of gender roles was tied to these historical events. This dynamic has an ongoing presence in American life, considering common attitudes toward Russia and China (among other countries still associated with the Soviet Union, despite its dissolution). Suburban architectural design is a manifestation of the isolationist, hyper-individualistic lifestyle so common in our capitalist society. Discouraging community among neighbors extends to a larger attitude of discouraging identification with the people of foreign countries. We see this now with Palestine.

House Beautiful is explicitly representational and politically charged in contrast to the body of work in the Abstract-Expressionist movement preceding it, which (while widely celebrated) was critiqued as cold, isolated, and overly intellectualized. As the first specifically American art movement to be recognized internationally, Ab-Ex could be considered a manifestation of a uniquely American cultural climate and value system. It emphasized masculine action and hyper individualized self-expression. It avoided scrutiny during the McCarthy era following the war due to its lack of representation, which was perceived as apolitical. A quote which I consider the most accurate summary of its faults comes (ironically) from Harold Rosenberg, who coined the term Action Painting3 and was one of the movement’s most avid supporters: “The gesture on the canvas was a gesture of liberation from value—political, aesthetic, moral.”3 This encapsulates the sentiment of the phrase “Art for Art’s Sake”, or, “l’art pour l’art,” a slogan coined in the early 19th century by French philosopher Victor Cousin4, which was popularized by those in opposition to Marxist aims of utilizing art for political purposes.

The ideological presence of “art for art’s sake” has persisted through numerous movements. As a variation of this philosophy, Italian Futurists also aimed to separate art and the consequences of the present from its context in the past, based on a desire to advance Italy’s position as a global power. They glorified speed and violence; Filippo Tommaso Marinetti refers to war in the Manifesto of Futurism as the “sole cleanser of the world”5, framing war as a natural evolutionary state. Many Futurists therefore supported the spread of fascism as an extension of this ideology.6

Walter Benjamin’s seminal essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, explores this concept in depth; he writes, “With the advent of the first truly revolutionary means of reproduction, photography, simultaneously with the rise of socialism, art sensed the approaching crisis which has become evident a century later. At the time, art reacted with the doctrine of l’art pour l’art, that is, with a theology of art. This gave rise to what might be called a negative theology in the form of the idea of ‘pure’ art, which not only denied any social function of art but also any categorizing by subject matter.”7 He then goes on to say, more explicitly, “This is the situation of politics which Fascism is rendering aesthetic. Communism responds by politicizing art.”8

House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home is indicative of greater trends in the evolution of artmaking: the growing popularity of mixed media and the increased importance placed on the role of philosophy and social issues in art, as advancements in technology rendered its former priorities somewhat obsolete. The question of removing images from their material context became a focus of contemporary artists following the Industrial Revolution, during which mechanical reproduction altered not only the physical properties of art but our approaches to conceptualizing it. Contemporary art movements became increasingly preoccupied with bringing attention to the viewer’s subjective perspective, encouraging the audience to cultivate a sense of self-awareness.

The representational qualities, cut-out style, and color palette of Martha Rosler’s work seem to reference the stylized look of Soviet propaganda posters (similar to the iconic, widely identifiable aesthetic of her contemporary Barbara Kruger). Martha Rosler says in a 2016 interview for Another Gaze Journal, “I was trained as an abstract painter, and I was liberated from that paradigm when Pop appeared; it caused me to question what is representation and what is art.”9 It interests me that she uses the word “liberated”, implying that abstract painting was a restrictive force, when abstract art movements are so often presented from the opposite perspective: as liberation from the shackles of representation. When asked to differentiate between making activist work as an artist and being an activist during an interview for BmoreArt in 2019, she replied, “To be an activist you probably have to be working intensively with a specific community and a specific issue or set of issues, specific outcomes. And if not, you’re something else ... I am an artist. I make art. And I was also a full-time professor. Activism is an on-going process, and it’s true that I worked with activists on that project, but one thing is certain: activists don’t expect intractable problems to be solved by an exhibition or a political campaign and certainly not in six months.”10 This indicates an understanding of, and respect for, the importance of the distinction between the spheres of material impact and cultural ideology. Placing emphasis on the primary role that the material occupies is characteristic of Marxist theory, reflecting the model represented in dialectical materialism where the means of production and technological tools serve as the foundation for culture.

As a prominent figure in the Feminist art movement, Martha Rosler could be compared to her peers on the basis of dealing with gender politics; however, what sets her apart is the extension of her work to include international politics such as anti-war activism and class consciousness. In an interview for The New York Times regarding the opening of her retrospective at the Jewish Museum, Martha Rosler describes some of her politics as rooted in her Orthodox upbringing: “There’s no question my sense of justice came from my religious background. If you think about Judaism, this is a really central component. It has to do with just behavior and a certain kind of righteousness and communitarianism.”11 While the second wave feminist movement focused primarily on bodily autonomy (largely that of white, middle-class women located within the United States) Rosler broadened the scope of this discussion to embody collectivist values by including other mechanics of domination as an exploration of the ways they were connected and contributed to each other. Elizabeth Richards identifies one aspect of this distinction in Materializing Blame: Martha Rosler and Mary Kelly, an article for Woman’s Art Journal, when she writes “Rosler’s combinations are a reminder that all images in the media, whether of a brutal war or pleasing domestic furnishings, are presented to the American viewer for consumption as spectacle.”12 Richards compares the way abstraction is used by Mary Kelly to the way Martha Rosler fully embraces the visual language of that spectacle in order to satirize it.

In House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, parallels drawn between American capitalism, commodity culture, and the Imperialist forces they fund highlights the contradictory position that American housewives were in. Despite their subjugation (largely presented as marketed objects themselves) they possessed a great deal of control over the economy through their collective buying power. As the people responsible for most household spending, they weaponized this power through boycotting. In 1966, as grocery prices rose due to inflation caused by government spending related to the Vietnam War, many housewives and female labor activists organized a national grocery store boycott to force prices back down in favor of working-class families.13

Martha Rosler connects the visual lexicon of American advertising with documentation of the Vietnam War in order to make the population aware of the underlying relationship between the two. As Carl Jung said, “The psychological rule says that when an inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside, as fate. That is to say, when the individual remains undivided and does not become conscious of his inner opposite, the world must act out the conflict and be torn into opposing halves.”14 Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious could also be framed in the context of dialectical materialism, a major component of Marxist theory, based on the writing of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The two share similarities in the illustrative diagrams used to demonstrate them, with a material foundation (the means of production versus the collective unconscious) and more individualized consequences of that foundation (institutions which shape values/ethics versus the personal unconscious and ego). Freud’s theories also follow this format, the foundation being material bodily processes shaped during development in childhood (oral, anal, Oedipal, latency, and genital) and their various effects on various personality traits in adulthood. Despite modern criticism directed toward their accuracy and lack of supporting evidence, Freud’s contributions have made an undeniable impact on the structure of clinical psychology.

The body of Marshall McLuhan’s work (a pioneer in the field of media theory) deals largely with materialist principles stemming from Marxism in the context of treating media as a physical extension of human sensory perception which shapes our approach to interacting with the world. In Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, McLuhan writes, “I am curious to know what would happen if art were suddenly seen for what it is, namely, exact information of how to rearrange one’s psyche in order to anticipate the next blow from our own extended faculties.”15

Located at the intersection of the art world and medical industry, the field of art therapy takes a great deal of inspiration from all of these sources in particular. Art therapy combines art practice and social activism with the key principle that artmaking is a fundamental human activity, as opposed to one reserved for those who are particularly wealthy or innately talented. It emphasizes the benefits gained through the artistic process, rather than imposing an assessment of technical skill. The value in art therapy is derived from the potential for art to illuminate thoughts and feelings, connect with others, or manage behavior. I consider art therapy the culmination of all aforementioned art historical context, as a fusion of mixed media art practice, community-focused activism, psychology, and philosophy.

Christine Givens is a writer and multimedia visual artist based in Tallahassee, Florida. Her poetry and soft sculpture explores themes such as institutional critique, dialectical-materialism, and generational trauma. She studied Studio Art and Psychology at Florida State University, with interest in the advancement of art therapy as a means for regaining agency and developing self-awareness. Her work has been featured at 621 Gallery in their First Impressions exhibition. Most recently, she incorporates her experience working in social service. She feels strongly about the importance of praxis and devotion to community. She can be found and contacted on Instagram @deathcabforcoochie

Hopkins, Budd. “Modernism and the Collage Aesthetic.” New England Review (1990-) 18, no. 2 (1997): 5–12. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40243172.

Fleming, D. F. “Vietnam and After.” The Western Political Quarterly 21, no. 1 (1968): 141–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/446519.

Rosenberg, Harold. The Tradition of the New, Chapter 2, “The American Action Painter”, pp.23–39

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “art for art’s sake.” Encyclopedia Britannica, January 23, 2015. https://www.britannica.com/topic/art-for-arts-sake.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. Manifesto of Futurism: Published in Le Figaro, February 20, 1909, 1983.

Bowler, Anne E. “Politics as Art.” Theory and Society 20, no. 6 (December 1, 1991): 763–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00678096

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” SAGE Publications Ltd EBooks, 1935. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446269534.n3.

Benjamin.

Rosler, Martha. Another Gaze Journal. “In Conversation with Martha Rosler (Interview),” February 24, 2016.

Ober, Cara. “Martha Rosler: Art as Activism, Democratic Socialism, and the Changing Role of Women Artists as They Age.” BmoreArt, January 22, 2020. https://bmoreart.com/2019/07/martha-rosler-on-art-as-activism-democratic-socialism-and-the-changing-role-of-women-artists-as-they-age.html.

Haigney, Sophie. “Martha Rosler Isn’t Done Making Protest Art.” The New York Times, November 6, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/06/arts/design/martha-rosler-jewish-museum.html.

Richards, Elizabeth. “Materializing Blame: Martha Rosler and Mary Kelly.” Woman’s Art Journal 33, no. 2 (2012): 3–10. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24395283.

Scott Nunn StarNews Staff, Wilmington Star-News. “1966: Inflation Sparks Grocery Store Boycott.” Wilmington StarNews, November 15, 2016. https://www.starnewsonline.com/story/lifestyle/around-town/2016/11/21/back-then-1966-inflation-sparks-grocery-store-boycott/24504448007/.

Jung, C. G. Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 9 (Part 2): Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. Princeton University Press, 2014.

McLuhan, Marshall. “Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man.” American Quarterly 16, no. 4 (January 1, 1964): 646. https://doi.org/10.2307/2711172.

Bibliography

Bartley, Russell H. “The Piper Played to Us All: Orchestrating the Cultural Cold War in the USA, Europe, and Latin America.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 14, no. 3 (2001): 571–619. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20020095.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” SAGE Publications Ltd EBooks, 1935. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446269534.n3.

Bowler, Anne E. “Politics as Art.” Theory and Society 20, no. 6 (December 1, 1991): 763–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00678096.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “art for art’s sake.” Encyclopedia Britannica, January 23, 2015. https://www.britannica.com/topic/art-for-arts-sake.

Burstow, Robert. “The Limits of Modernist Art as a ‘Weapon of the Cold War’: Reassessing the Unknown Patron of the Monument to the Unknown Political Prisoner.” Oxford Art Journal 20, no. 1 (1997): 68–80. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1360716.

Deutsche, Rosalyn, Elena Volpato, and Martha Rosler. Martha Rosler: Irrespective. Yale University Press, 2018.

Fleming, D. F. “Vietnam and After.” The Western Political Quarterly 21, no. 1 (1968): 141–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/446519.

Haigney, Sophie. “Martha Rosler Isn’t Done Making Protest Art.” The New York Times, November 6, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/06/arts/design/martha-rosler- jewish-museum.html.

Hopkins, Budd. “Modernism and the Collage Aesthetic.” New England Review (1990-) 18, no. 2 (1997): 5–12. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40243172.

Jung, C. G. Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 9 (Part 2): Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. Manifesto of Futurism: Published in Le Figaro, February 20, 1909, 1983.

McLuhan, Marshall. “Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man.” American Quarterly 16, no. 4 (January 1, 1964): 646. https://doi.org/10.2307/2711172.

Ober, Cara. “Martha Rosler: Art as Activism, Democratic Socialism, and the Changing Role of Women Artists as They Age.” BmoreArt, January 22, 2020. https://bmoreart.com/2019/07/martha-rosler-on-art-as-activism-democratic-socialism- and-the-changing-role-of-women-artists-as-they-age.html.

Richards, Elizabeth. “Materializing Blame: Martha Rosler and Mary Kelly.” Woman’s Art Journal 33, no. 2 (2012): 3–10. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24395283. Rosenberg, Harold. The Tradition of the New, Chapter 2, “The American Action Painter”, pp.23–39

Rosler, Martha. Another Gaze Journal. “In Conversation with Martha Rosler (Interview),” February 24, 2016. Video Link

Rosler, Martha. “[Article by Martha Rosler].” Assemblage, no. 41 (2000): 69–69. https://doi.org/10.2307/3171329.

Scott Nunn StarNews Staff, Wilmington Star-News. “1966: Inflation Sparks Grocery Store Boycott.” Wilmington StarNews, November 15, 2016. https://www.starnewsonline.com/story/lifestyle/around-town/2016/11/21/back-then- 1966- inflation-sparks-grocery-store-boycott/24504448007/.

Stevenson, Janet N., and Paul Duncum. “Collage as a Symbolic Activity in Early Childhood.” Visual Arts Research 24, no. 1 (1998): 38–47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20715934.

Wark, Jayne. “Conceptual Art and Feminism: Martha Rosler, Adrian Piper, Eleanor Antin, and Martha Wilson.” Woman’s Art Journal 22, no. 1 (2001): 44–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/1358731