As featured in KAILON Magazines Fall/Winter issue “The December Edit”

Including additional previously unpublished questions.

Some artists speak loudly through the world, others speak quietly and let the work thunder on its own. Nikola Djukich is the latter. Even across continents with him answering my questions from the other side of the world, his presence comes through with a clarity you can feel. His words arrive with deep and true intention, not performance, but someone who lives by it and has lived it. Someone who understands exactly who he is, what he’s survived, and what he’s creating toward.

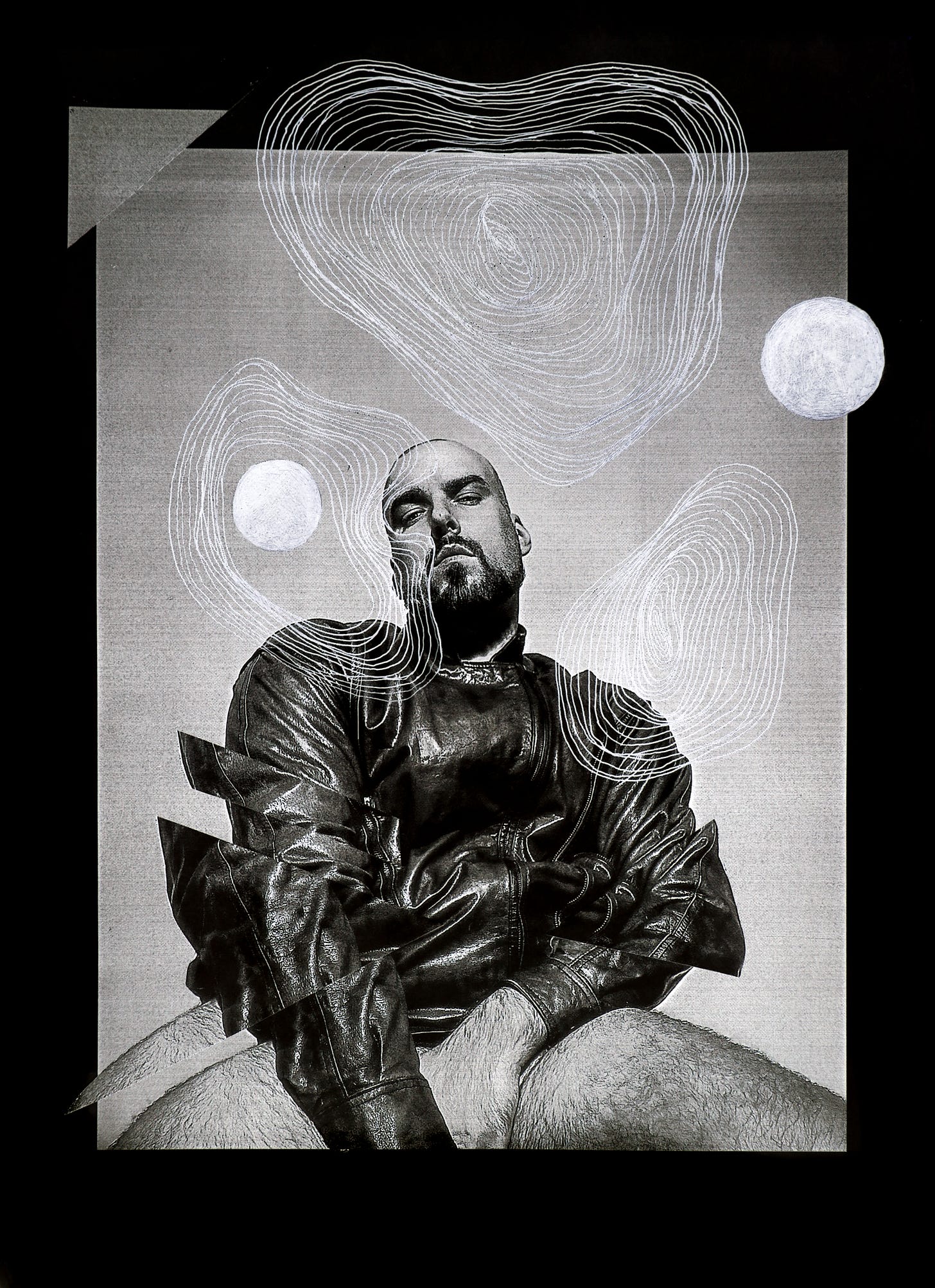

Born in Serbia and shaped by displacement, queerness, migration, and a relentless curiosity about the human body, Nikola’s work doesn’t just depict identity, it dissects it, reconstructs it, questions it, sometimes wounds it, and often heals it. His collages, portraits, and visual essays read like excavations, memory, archive, bone, lineage, and selfhood layered into something that feels both ancient and immediate.

What struck me most was not just the depth of his art, but the depth and stillness of his voice through his words. He answers like someone who has spent a long time learning the difference between truth and narrative, between survival and becoming, between the body that was inherited and the body he is actively building for himself.

This is Nikola—unfiltered, intentional, and deeply, defiantly human.

Personal & Artistic Roots

You grew up in Serbia, a place where every street, ruin, and phrase carries the weight of history. When you look back, how did that landscape shape not just who you are, but how you see the world and how you make art?

I think growing up in Serbia shaped me more than I even realized for a long time. It’s a place where everything carries some kind of heaviness — the streets, the faces, the stories people tell and the ones they never say out loud. You grow up surrounded by history that is both collective and personal, and it finds its way under your skin. Family life, for example, was never just family — it was a small reflection of the whole environment: the silence, the pride, the trauma, the shame.

I think because of that, I started to see art as a form of rebellion. My photographs, especially the erotic ones, were never about sex — they were about confronting that silence, about saying: I exist, my body exists, my desire exists, and I’m not going to hide it. It’s my way of standing against everything that told me to be quiet, to be less, to disappear.

When it comes to collage and mixed media, that comes from something else — from survival. Serbia teaches you to adapt, to make something out of nothing, to rebuild after things fall apart. So I learned to change mediums, to combine things that don’t belong together, to transform constantly — because that’s what you do when you grow up in a place that doesn’t give you stability.

And with drawing and painting, especially my self-portraits, that’s where I try to understand who I actually am under all of these layers — family, religion, nationalism, expectations, masculinity. My self-portraits are my way of asking: Who am I when I strip all of that away?

So, I think Serbia made me — but it also made me want to unmake myself, to rebuild who I am on my own terms.

At what point did art stop being a refuge and become a language in its own right, a way to speak across borders, across time, across silence?

I think art stopped being just a refuge very early — maybe even before I knew what art really was. Since childhood, I could feel that not everything around me made sense, that people said one thing and meant another, that love could exist in the same space as control, or silence, or shame. So I started building my own inner world where I could breathe, where things could finally be what they truly are.

At first, it was a kind of hiding — drawing, imagining, collecting fragments of something that felt more honest. But over time, it became a language. Not just a place to escape to, but a way to speak, to connect, to make sense of what was unsaid. It became the only language that could cross all those borders — between generations, between cultures, between the person I was told to be and the person I actually am.

Now, when I create, it’s not about hiding from the world anymore — it’s about translating it. Translating silence, fear, and desire into something that can be seen, touched, or felt. That’s when it stopped being a refuge and became a voice.

Do you feel that you or your work is still tethered to Serbia, to its past and its silences, or has it become a dialogue with the other worlds you’ve inhabited since leaving?

I think I will always be tethered to Serbia in some invisible way — not to its politics or its borders, but to its atmosphere, its silences, its contradictions. That place shaped the way I see everything: how I read faces, how I sense tension in a room, how I translate emotions into form. Even when I left, I carried that landscape with me — the heaviness, the beauty, the unfinished conversations.

But over time, I realized that I wasn’t just shaped by that place — I was also building my own. A world with its own logic, its own rhythm, its own language. Wherever I go, I live inside that world. It’s like an inner territory that travels with me. My roots are not in a country, but in that space I created — between what is real and what is imagined, between memory and transformation.

So, my work is no longer only about Serbia or about leaving it. It’s a dialogue between worlds — the one I was born into, and the one I’ve built for myself. And I think that’s where my art breathes: in that tension between belonging and becoming.

Life in Vietnam & Cultural Contrast

What brought you to Vietnam, and how did you know it would be a place where you could live, make art, and inhabit a new life?

A few years before coming to Vietnam, I was living in Shenzhen — a massive city, full of movement, lights, and noise. It was exciting at first, but over time, I started to feel consumed by it. Everything was fast — people, work, thoughts. I reached a point where I felt completely drained, like I couldn’t hear myself anymore.

Then a friend of mine told me she had moved to Vietnam — she described days by the sea, drinking coconuts, living slower, lighter. I remember that moment clearly because it sounded like the opposite of everything I was living. It wasn’t about running away, but more about touching the ground again, literally.

I came here because I needed to reset — to reconnect with nature, to breathe, to listen. Vietnam gave me that space. It allowed me to build silence around myself, a kind of inner quiet where new ideas could grow. It’s not just a place I live in now — it’s a space that reminds me that simplicity can also be a form of art.

When you first arrived, what struck you most, the textures of daily life, the rhythms of the streets, the smells, the sounds? How did it feel to land somewhere so different from Serbia?

When I arrived in Vietnam, I already had a sense of what to expect. After living for years in Shenzhen, I was familiar with the rhythm of this part of Asia — the markets, the colors, the sounds that never really stop. But Da Nang felt softer. The air was slower, and the sea was always there — that was new for me.

It wasn’t a shock, more like an exhale. Shenzhen had trained me to move fast, to adapt, but here I finally slowed down. I remember thinking that I could finally hear myself again. Compared to Serbia, it felt like I had already crossed that border long ago.

In what ways has living in Vietnam changed how you see the world, and how has that shift found its way into your work?

Living in Vietnam taught me how to slow down. Life here moves with a different rhythm — softer, lighter, almost suspended in time. In the beginning, I lived near the beach, and every morning I would watch the sea, drink coffee, smoke a cigar, and just be.

It made me realize how much I had forgotten the simplicity of existing without constant noise. That quietness started to appear in my work — in the pauses, in the silence between images. I think Vietnam gave me permission to breathe, and that changed the way I see everything.

Are there elements of Vietnamese culture, history, or daily life that have seeped into your visual language—colors, forms, or patterns that feel new to you?

I wouldn’t say I consciously use Vietnamese symbols or motifs, but I think the atmosphere — the colors, the humidity, the way light behaves here — slowly entered my work.

How do you navigate the contrast between the cultural memory you carry from Serbia and the reality of life in Vietnam? Do they clash, blend, or quietly inform each other?

For me, the cultural memory I carry from Serbia and life in Vietnam don’t feel like they clash—they quietly inform each other. Surprisingly, people here share certain similarities with those from Serbia. Despite being on another continent, there’s a traditional and conservative thread, but also a sense of openness to others. I think years of historical challenges, conflicts, and resilience shape people in ways that feel familiar. So even though I’m thousands of kilometers away from home, I notice echoes of Serbian mentality here, and it makes navigating this new life feel more natural than I expected.

Are there ways in which Vietnam has challenged or reshaped your understanding of identity, community, or belonging compared to what you knew growing up?

Vietnam hasn’t necessarily changed my understanding of identity or community, but being far from home has reshaped how I experience them. I realized that my sense of home isn’t tied to a place—it’s something I carry within myself. Living here, slowing down on the beach, drinking coconuts, and seeing life at a different pace is something I didn’t have growing up in Serbia.

I’ve also met people who travel the world, building communities far from their countries of origin. Seeing how they navigate belonging and connection reshaped my own perspective. Even though I’ve been more stationary here in Vietnam over the past couple of years, being part of this broader, mobile world has expanded how I think about home, identity, and community.

Do you feel your work is now in conversation with Vietnam itself, or does the country serve more as a lens through which you see and reinterpret your own roots?

I would say Vietnam mostly serves as a lens through which I see and reinterpret my own roots. The environment, the slower pace, and the cultural context give me space to reflect on my past, my family, and my experiences growing up in Serbia. It doesn’t directly dictate my work, but it offers a perspective and a distance that allows me to explore my identity, memory, and heritage in a different way. Vietnam becomes part of the process—not the subject—but a place that shapes how I see and translate my own story.

Looking back, what has been the most surprising lesson from living in Vietnam, something you didn’t anticipate that has altered your art or your perspective?

The most surprising lesson from living in Vietnam has been realizing how much slowing down and simply being present can change perspective. Being able to go to the beach, relax, and enjoy the moment gave me space to focus on my mental health and reflect on past experiences—something I didn’t have the time or space for in Shenzhen or in Serbia. That slower pace allowed me to understand myself better, and it immediately influenced the way I approach my art. Just having the chance to pause and be centered has reshaped both my perspective and my creative process.

Identity, Language & Cultural Memory

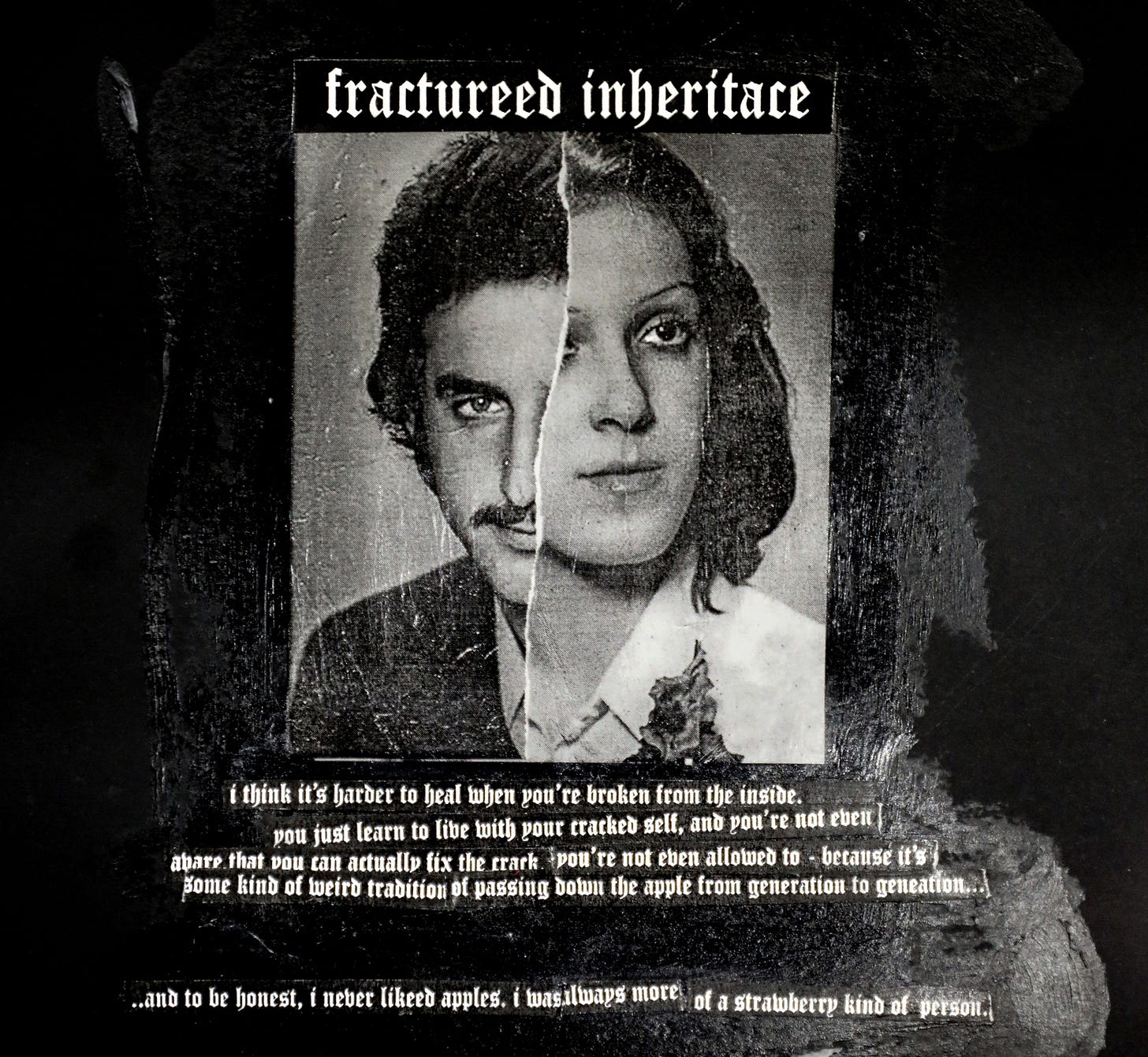

You often layer Cyrillic and Latin scripts, two alphabets that seem to carry centuries of tension and belonging. What does that weaving mean to you now? Is it reconciliation, resistance, or something more porous?

I don’t use both scripts very often, but recently I started exploring Cyrillic more. I’ve been experimenting with writing my name in Cyrillic and combining it with my name in Latin, sometimes in collage works. I’ve also been incorporating some prayers and images of religious symbolism into these pieces. It feels like reclaiming a part of myself I wasn’t really in touch with before. In some of my recent projects, which deal with family and generational trauma, using Cyrillic for my name and these symbolic elements felt more natural and meaningful—it adds another layer of personal and cultural resonance to the work.

Language is intimate and political. When you use typography, scripture, fragments of text, are you reclaiming your own voice or documenting the fractures of diaspora?

For me, using different scripts and fragments of texts is both intimate and political. It’s a way of reclaiming my own voice, but it’s also about documenting the fractures of history and family—the layers of diaspora and generational trauma that shape me. By combining Cyrillic and Latin, or layering prayers and personal writing with visual elements, I’m exploring identity in a way that’s deeply personal, but also connected to cultural memory. It’s a balance between asserting my presence and reflecting the dislocations and gaps that exist in my own story.

In your art, where does personal memory end and collective memory begin? Are they distinct currents, or parts of the same river you move through?

For me, personal memory and collective memory are part of the same river—they constantly flow into each other. My work often starts with very intimate experiences, family stories, or my own body, but those personal fragments inevitably connect to larger histories, cultural memory, and the experiences of the diaspora. When I use scripts, prayers, or symbolic imagery, I’m tracing both my own path and the broader currents that have shaped my family and culture. The line between the personal and collective isn’t fixed; it’s fluid, and I move through it in my work.

Generational Trauma & Sexuality

Your work often circles inherited trauma, the things we carry but do not speak aloud. How do you approach that weight without letting it define the entire piece?

Until recently, I didn’t approach generational trauma directly in my work. My earlier pieces were more rebellious—they were shaped by anger, frustration, or the residual shame that trauma brought into my life, but they weren’t intentional explorations of it. That anger, that rebellion, was how the trauma surfaced indirectly in my work. It defined the energy of the pieces without being the explicit subject.

Only recently have I started engaging with these themes consciously. I’ve begun creating works—like collages and layered compositions—that directly reflect on family history and generational trauma. These pieces aren’t about victimhood; they’re about witnessing, understanding, and representing what shaped me. They are literal in a way my earlier work wasn’t, telling stories of inherited weight while still leaving space for complexity and nuance.

Approaching trauma this way allows me to carry its weight without letting it dominate everything. I’m not defined by it, but I acknowledge it, explore it, and translate it into a language that feels honest. It’s a balance between confronting difficult truths and maintaining the full spectrum of who I am, both in the work and beyond it.

Queerness in your work feels like a pulse, fluid, coded, layered. How do you translate sexuality into form, into texture, into symbol?

I don’t usually think of queerness as a separate topic to explore—it’s just part of who I am. Being gay naturally informs the way I see, create, and experience the world, so it becomes part of everything I do. I’m not defined by my sexuality, but it shapes the perspective from which I approach my work.

How it shows up depends on the medium. In collages dealing with family abandonment or trauma, it’s less about sexuality in a literal sense and more about witnessing and processing experiences that are deeply tied to my life as a gay person. In photography, it can be more explicit and openly sexual. In music or portrait work, sometimes I’m channeling not just my own sexuality but also the sexuality of the people I photograph or collaborate with.

Queerness in my work isn’t a theme I impose—it emerges naturally. It’s in the forms, textures, and symbols I use because it’s inseparable from my perspective and my way of being. Without it, the work wouldn’t feel honest or whole.

Does being both queer and diasporic offer a particular vision, a kind of double consciousness, inside the tradition, yet outside of it at the same time?

I have to admit, this is a really interesting question because I haven’t thought about it explicitly before. But looking back, even when I was living in Serbia, I never felt fully part of society. Being queer meant I was always somewhat on the outside. In that sense, I think this double consciousness is something many queer people experience from a young age—we learn to adapt, to live in two worlds at once.

For me, it’s also connected to tradition. There’s one part of myself that exists within cultural norms, and another part that rebels against them, that creates its own space—my artistic self. These two currents coexist constantly. I carry the tradition and memory of my culture, yet I interpret and transform it through my own lens. Being both queer and diasporic gives me that perspective: rooted in, yet simultaneously outside, a framework that I both inherit and challenge.

Body, Myth & the Cover Art

For the Kailon cover, you described a work that touches on body image, acceptance, and Nike, the goddess of victory. How did those threads of flesh, divinity, self, come together in this piece?

For the Kailon cover art, the piece came from a very personal and transformative place. I started with an image of Nike, the Greek goddess of victory, as a kind of structural and symbolic anchor. From there, I layered different images of my body and my friend Nika’s body—photographs we had taken over the years, fragments of ourselves. It was very much about the body as a site of experience, vulnerability, and identity.

The work emerged after a conversation with my friend about our experiences with anxiety and panic attacks. For months, I felt like I was going through it alone, but reconnecting with him and hearing his story made me feel seen, understood, and less isolated. That relief, that shared experience of struggle and survival, became central to the piece.

Through this layering—of flesh, of personal history, and of the goddess Nike—I wanted to capture a sense of transformation, acceptance, and victory. It’s about witnessing ourselves, acknowledging the challenges and the trauma, and still celebrating life and resilience. The threads of flesh, divinity, and self come together as a reflection of survival, friendship, and the reclaiming of personal power.

The body in your work often functions as both image and archive. How do you approach it as a repository of history, memory, and desire?

For me, the body is inseparable from memory and history—it’s both an image and a living archive. Each body, including my own, carries traces of personal experience, family history, trauma, desire, and identity. When I work with images of the body, or even fragments in collage, I’m engaging with that archive. I layer moments from different times, different experiences, and different bodies to reveal not just physical form, but the emotional and cultural narratives embedded in it.

The body becomes a way to witness and hold stories that might otherwise remain invisible. It’s about desire, vulnerability, and memory coexisting with form, creating a record of how we’ve been shaped, who we’ve loved, and what we’ve carried. In that sense, the body in my work is never just a body—it’s a living repository of self, history, and connection.

Nike represents triumph. Do you see this piece as a kind of victory, over self-doubt, over expectation, or over the gaze of others?

Yes, I see this piece as a kind of victory, but not in a literal or final sense—it’s more about self-recognition and resilience. It came out of a conversation with my friend Nika after a few years of not communicating. The timing felt almost fated; we reconnected right when we both needed to share our experiences with anxiety and panic attacks. Through those intense exchanges over a couple of days, I realized how much we had both endured and survived.

That inspired me to immediately start working on the collage, intertwining our bodies into the form of Nike, the goddess of victory. The connection between our names—Nika and Nikola—made it even more symbolic. The piece represents a triumph over self-doubt, over isolation, and over the anxiety that had weighed heavily on us. It’s about two people witnessing each other’s survival and claiming that, despite the chaos, everything is going to be okay. That was the emotion and sense of triumph I wanted to capture.

Artistic Process & Visual Language

Your collages feel like layered landscapes of memory, history, and desire. How do you decide what must appear, and what remains hidden?

Most of the time, I don’t consciously decide what must appear and what remains hidden. When I’m making a series of collages, the other works in the series often guide how each piece evolves. Sometimes, when I feel a collage isn’t working, I start over, tear it apart, or reassemble it in a new way. I’m constantly seeking balance between memory, history, and desire—each element informs the others, and the work emerges through that tension. It’s less about strict control and more about finding harmony between what is revealed and what remains concealed.

How do you know when a piece is complete? Is it closure, or simply a pause in an ongoing conversation with the work?

I struggle a lot with closure, and sometimes I even have to push myself to finish a piece. In an ideal world, I could work on something indefinitely—some of my works, like a self-portrait I started in 2014 or 2015, have evolved over ten years with countless layers of paint and faces. That piece is very intimate, something I don’t show publicly, and I keep adding to it whenever I feel like it.

When it comes to presenting work, I try to be more realistic and intentional about finishing. Sometimes, a piece in a series might feel unfinished on its own, but it makes sense in the context of the series as a whole. Other times, I have to remind myself to stop, even if it doesn’t feel “perfect,” and accept that it’s enough for now.

This struggle extends to how I present my work, like on Instagram. I often delete and restart my entire feed because I can’t decide how to show the work, which isn’t ideal, but it sometimes helps me gain a new perspective. Ultimately, I see completion less as final closure and more as a pause—a way to step back and continue the ongoing conversation with the work.

Material itself, paper, ink, texture, carries meaning in your hands. How do these choices help you translate the intangible: memory, sexuality, grief, joy?

Since I recently started working with collage, I’m still exploring how material itself—paper, ink, texture—carries meaning. In my previous photography and drawing work, symbolism and meaning were always central, so I was used to finding it in purely visual elements. With collage, I’ve had to translate that same understanding into tactile materials, to feel and manipulate the meaning through texture, paper, and physical layering.

Not every paper is the same, and each surface has its own qualities. Most of the time I use cheap black-and-white prints from a simple printer, and I layer them with old notes, family photographs, or scraps from my scrapbooks. I explore textures, contrasts, and subtle symbolism—mostly monochromatic, sometimes punctuated with gold to create a sense of depth or reference to icons and memory.

Through these choices, I try to make the intangible tangible: memory, sexuality, grief, and joy all find expression in the material itself. The process is about discovering the emotional resonance in what I can touch and manipulate, translating feelings into a physical language that speaks as clearly as images alone ever could.

Wider Reflections

Your work resonates strongly with queer and diasporic audiences, yet it also reaches beyond those circles. Do you see art as a bridge or a mirror or both?

I see my work as both a bridge and a mirror. For queer and diasporic audiences, it can reflect shared experiences, struggles, and memories—a mirror that validates and witnesses. At the same time, I hope it can also function as a bridge, inviting others outside these communities to engage with perspectives and histories that might be unfamiliar. I try not to create work that’s didactic; instead, I aim for honesty and intimacy, and through that openness, people from different backgrounds can find connection, empathy, or even just a glimpse into experiences that aren’t their own.

What do you hope lingers in a viewer, beyond the visual, in the body, in the spirit?

I try not to hope for a specific reaction from the viewer. Early in my photography work, I was focused on provocation and knew how to elicit a reaction, but over time I realized that’s not the point. My work is about expressing myself authentically. If a viewer finds something meaningful, relatable, or inspiring in it, that’s wonderful—but I don’t create to satisfy anyone. I make the work I need to make, and whatever lingers with someone beyond the visual or into the body and spirit is a gift, not a goal.

If you could leave one message for the next generation of queer artists, anywhere navigating layered identities, what would it be?

If I could leave a message for the next generation of queer artists, it would be to stay true to yourself and your authentic voice. Especially today, when everything moves so fast and social media often sets the pace, it’s easy to get caught up in trying to please others or meet expectations. But the most important thing, at least for me, is to make work that is honest and meaningful to you. Be a little selfish in your art—create because it matters to you, because it expresses who you are. That authenticity is what gives your work life and resonance, and it’s the best guide not just for art, but for living fully and truthfully.