This piece is written in both English and Russian, the Russian translation is available below after the English version.

We’re meeting at Alexanderplatz, under the clocks—Berliners don’t need any further explanations on the location of the meeting place. For half a century, the Weltzeituhr (World Clock) has been counting down the time in 146 cities and regions around the globe, a symbol of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) empire and its vast ambitions. Locals arrange meetings here, street musicians compete for the public’s attention, tourists take photos with the iconic view, food delivery drivers stop by in the shade for a smoke break, and the police closely guard the established order, but few people give a second thought about the symbolism of this monument, let alone the history of the square.

Marina Solnzewa and Denis Esakov, founders and curators of the de_colonialanguage collective, agreed to share the story of their large-scale art initiative, the Open Air Museum of Decoloniality, which has turned Berlin’s main square into a free museum:

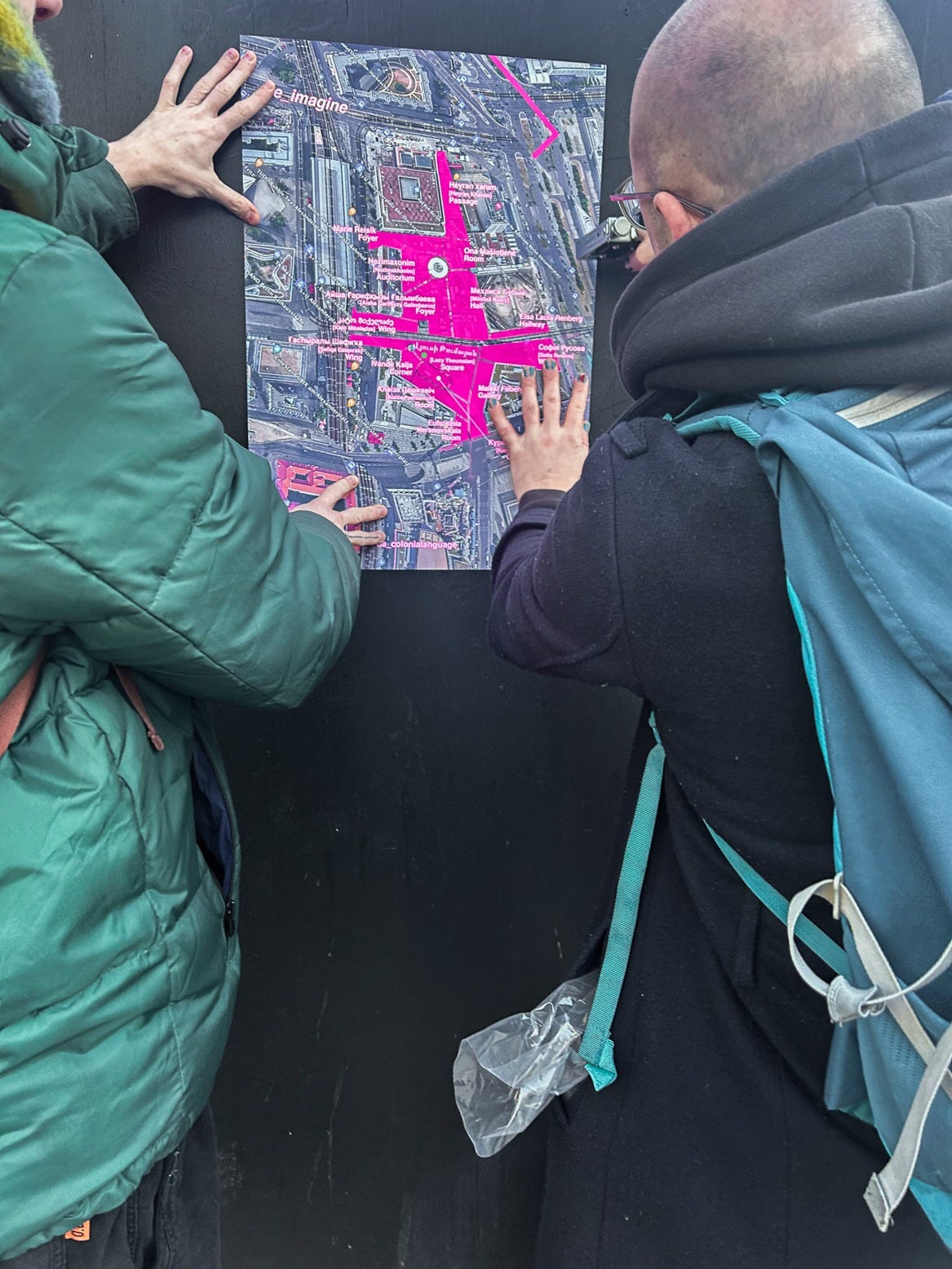

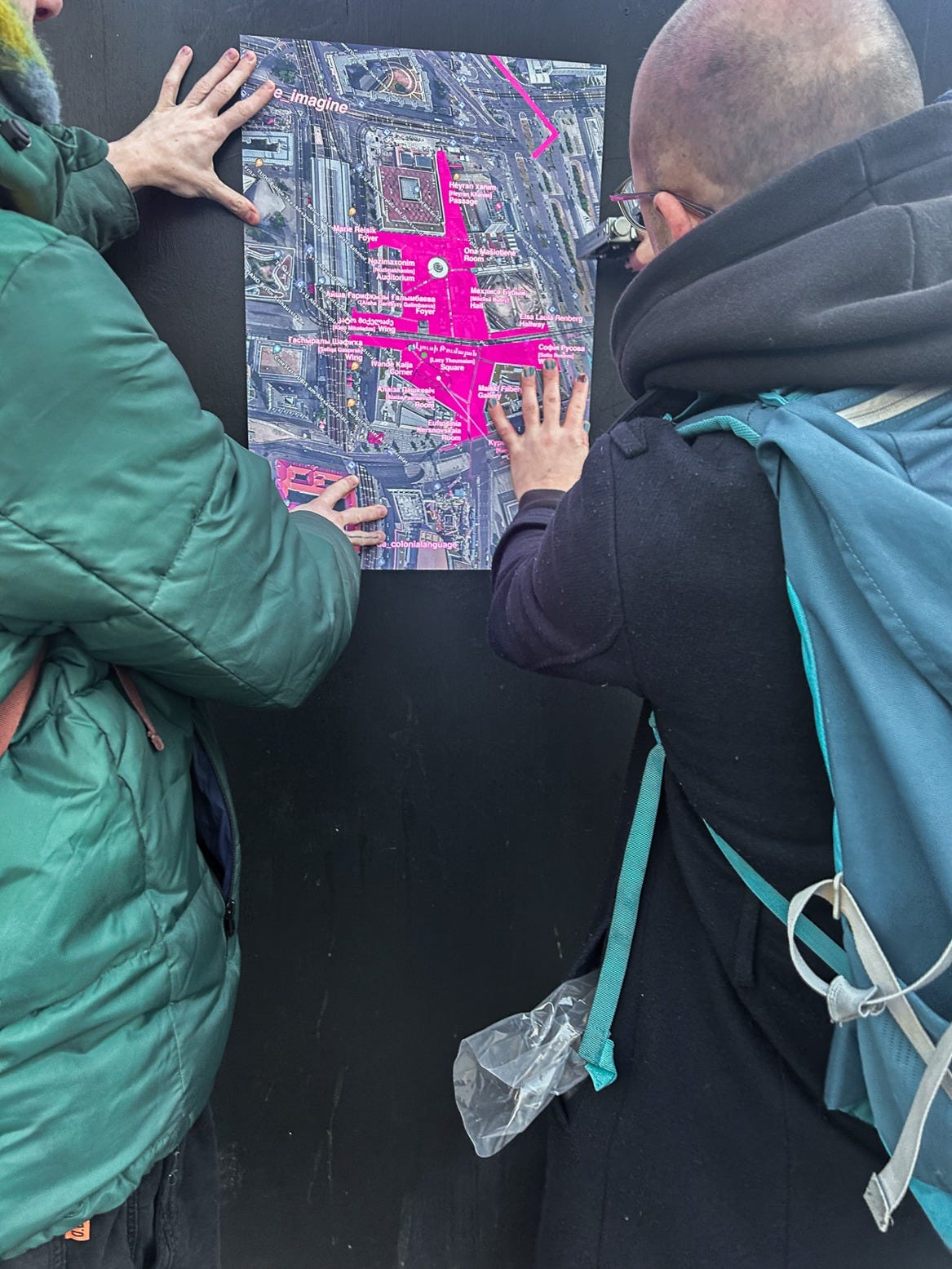

“The first action we did here was named ‘Who the fuck is Alexander?’. We hung banners saying ‘Who the fuck is Alexander?’ in different parts of the square and started asking people: ‘Do you know who Alexander is?’ We expected them to mention some German Alexanders, such as Alexander von Humboldt... but for some reason, people more often mentioned Alexander the Great. And no one knew that the square’s name was dedicated to a Russian tsar.”

“We came up with the idea: the square has to be renamed. It is very strange in 2022, when Russian imperialism is on the march and waging a military campaign to conquer new lands, to see here, in the center of Europe, a square, one of the most gigantic squares, which still bears the name of Russian imperialism. Alexander I was a highly successful colonizer: during his reign, he annexed a vast amount of land in Central Asia and Eastern Europe. It is weird, isn’t it? At the very least, it sounded like an invitation to us, and Alexanderplatz seemed like a good place to develop critical theory.”

The scattered museum format was also chosen for a certain reason:

“First of all, it was funny – calling the square ‘a museum’ was a joke to us, playing at being a museum... Then we started criticizing institutions and institutionalism by creating our own museum like this, in the square, and doing whatever we wanted there.”

“Secondly, a decolonial critique of museums is now an important part of the discourse. We thought: what if, for example, a museum without walls would exist or a museum where events are held? If we regularly organize small events, then time becomes the most important factor, because if you do something regularly, you turn yourself into a sustainable institution, even if it has no walls. In this way, we tried to criticize the concept of the museum from this point of view.”

Marina and Denis admit that they did not immediately come up with the interactive, engaging format of their “museum,” but gradually felt their way toward an interactive approach to the space of the square and its visitors:

“We noticed this difference when we moved from an enclosed location to an open space. In a gallery, there are unwritten ‘white cube’ codes. You’re aware that you can’t touch anything, but if you come to the opening, you’ll probably get a drink. You know all these rules, they’re in the air, you kind of know the code of conduct, how to behave in a ‘white cube’, whatever it may look like. But in the square, there is no such code.”

“At first, it was like that: we are an art collective, and we are going to hang our work. But then we quickly came up with an open format called ‘toolbox’, or ‘gamefield’, and since then we have never done the work exclusively on our own—we just prepare a set of tools and materials, deploy them in the space, and people join the suggested activity. We set a certain theme: for example, “Who are the Others in society?” So we made a banner: “Who is the Other”, and then we had a field and paper, markers with which one could express their feelings about who the others are or what their feelings were when they felt like an outsider. And people connect with this very easily, because most often it’s a very open and simple question, not very sophisticated, instead – always appealing to some kind of personal experience.”

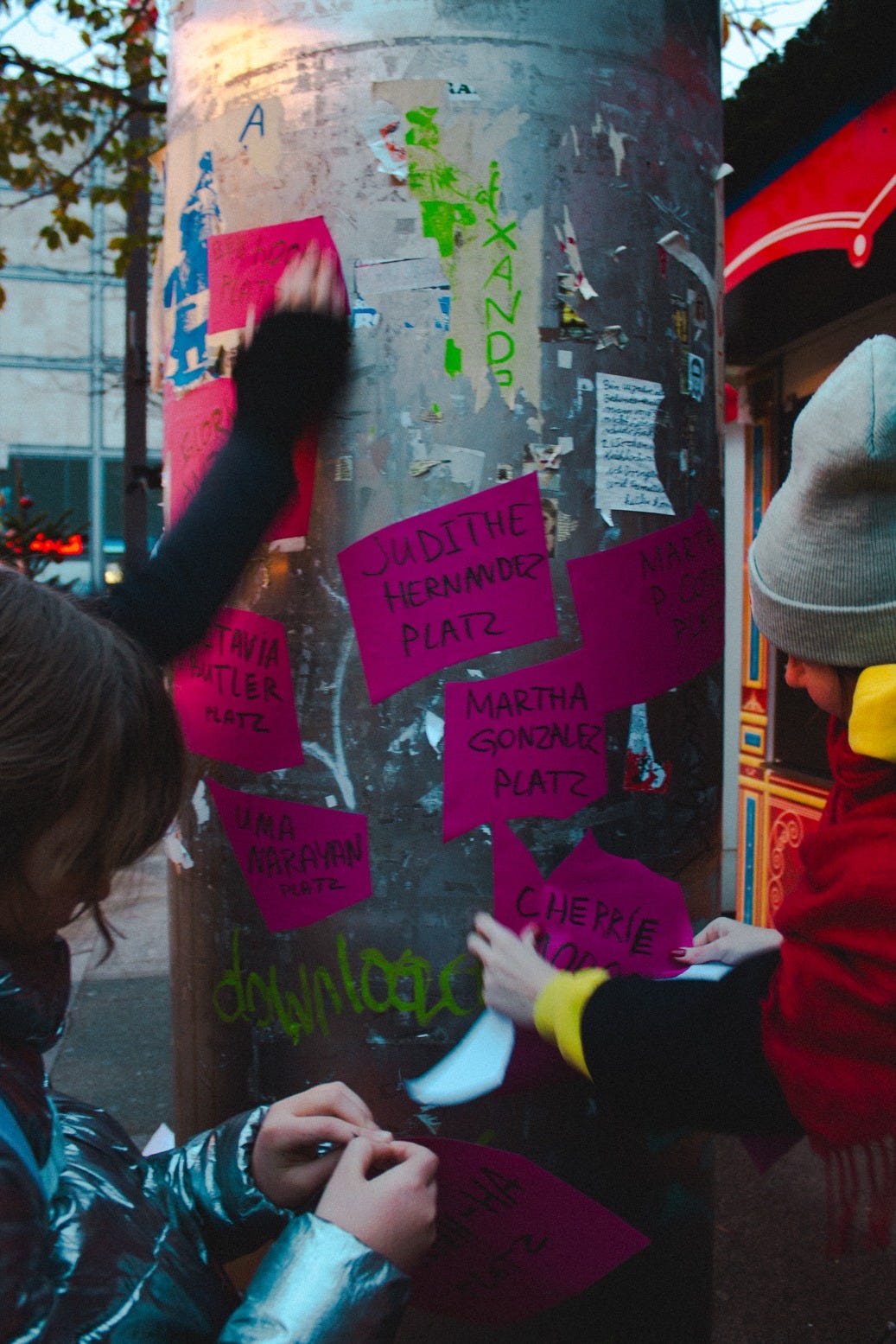

“There was a very cool thing at one of our first events, which was back in 2023. We called it ‘Other Names’, based on the idea that the square should be renamed. And we decided to do such a public research: we brought pink tape and started writing the names of feminists from all over the world on it. The list included Chicano feminists from Mexico, Black American feminists, feminists from Russia, Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and Africa. We looked at where and when they were active, what they achieved, and wrote their names on that tape. We started right at the subway station because it was the end of November, already dark and nasty cold. We spread out the tape, taking up part of the passageway.

“The BVG security guards scolded us a little, but we announced ourselves as artists, and they kind of came to terms with this fact. Then we cut the tape into individual names and went out to Alexanderplatz. There is a ventilation shaft up there, a shiny metal ‘totem pole’ four meters high. We started to stick these names onto it. We were joined by some women who read the names, immediately understood who these people were, asked, ‘Oh, let us help you!’ and started sticking names onto the pole too. And it was as high up as one can reach—a little over two meters—completely covered with these pink names, the pole was turned completely pink, and this work lasted for approximately six months.”

“If you offer a toolbox, people immediately join in the conversation, and the field of sharing and exchange becomes very generous. In the end, the final work is always created by an insane number of people on Alexanderplatz. That’s usually more than 100 hands that have joined in, contributed something, done something, and the result turned out to be a voluminous, multifaceted statement.”

Despite less opportunities for art in recent years due to Berlin’s budget cuts, artists are finding new ways to be heard: the open-air museum is one of them. Marina and Denis are convinced that a return to precariousness can, to some extent, become a motivating factor: artists go underground and begin to create truly independent art.

The downside of this trend is the need to seek cooperation with the authorities and the police. The team has mixed experiences in this area: on the one hand, Berlin still positions itself as a cultural hotspot, so the police are tolerant even towards unauthorized actions, as long as they do not carry any explicitly political statement.On the other hand, there is a clear commercialization of public spaces going on, and Alexanderplatz is a striking example of it; not a week goes by without some kind of fair, fashion show, or other “folk” festival being held on the square.

Skyscrapers, strict regulations on permitted activities, and commercial street art that does not allow for any co-creation deprive public space of its direct function as a gathering place for ordinary citizens. Over several art happenings, the collective has built relationships with all the regulars at Alexanderplatz and, to their surprise, discovered that tourists are not its main demographic:

“There is a large Polish community living in these panel buildings <behind Alexanderplatz>, and, accordingly, there are a lot of Polish teenagers and people from the Polish diaspora here. There is a big number of homeless people living under the bridge and around the train station, who also use this place. In the summer, they take a wash in the fountain, and they can always find some food here or ask people for small change. The homeless people very often and very generously share their stories, which are incredibly scary. There are many religious people here, Jehovah’s Witnesses, for example. They literally come to us every time with sermons and blessings, and they are also very active, but at the same time quite one-way in their communication…”

“The daily routes of local residents always go through the square. Academics often walk here and, seeing our work, note that it may intersect with their field of scientific research in some way. Alexanderplatz actually has a very diverse audience.”

From September 2023 to September 2024, de_colonialanguage held thirteen events. In 2025, there were six additional performances, united under the title “Voices Otherwise” and enriched by five guest artists from Chuvashia, Armenia, the North Caucasus, Tatarstan, and Kazakhstan. In 2026, the collective plans to continue its interventions:

“In the spring and summer, we are planning to do a “Political Wardrobe”. We’ll develop templates and bring materials: different fabrics and paper that can be used to make clothes. The central idea of the action is that these clothes should express political preferences, interests, and statements. You can write something, you can make an outfit in the colors of a flag, or create some kind of form that can be interpreted as something that reflects your political views... In other words, we will explore how fashion can be political, and we plan to hold at least three such ”Political Wardrobes”. All this will take place here, on Alexanderplatz. And at the end of the event, we will have a fashion show.”

When asked whether art can still be a powerful political statement in our time and age, Marina and Denis answer unequivocally:

“Art is always political – perhaps there is no such thing as apolitical art, because everything that is part of our lives already has some kind of political significance. And now, it seems, especially so.”

“When public space shrinks, you need to find new places where you can meet other people and have important conversations. Even the act of cooking together can become political.”

The idea of organizing such an event—a collective kitchen in the middle of Berlin’s central square—is also seen by de_colonialanguage as a continuation of their already quite successful Museum of Decoloniality project.

Their story sets a great example that destroying barriers is always more fruitful than building them up, whether between people, nations or institutions.

You can find out more about the collective’s past and future events at: https://www.instagram.com/de_colonialanguage/

English version edited by edited by Grace Myatt and Lilli Eve

превращая площадь в искусство

Мы встречаемся на Александерплац, под часами – берлинцам и берлинкам не нужно объяснять дважды, где это. Барабан Weltzeituhr, часов мира, вот уже полстолетия не перестаёт отсчитывать ход времени в 146 городах и регионах мира, ГДРовский символ империи и ее не ослабевающих амбиций. Местные назначают здесь встречи, уличные музыканты – борются за внимание публики, туристы – делают фото на память, доставщики еды – останавливаются в тени на перекур, полиция пристально охраняет сложившийся порядок, но мало кто задумывается о символике этого памятника, тем более – об истории площади.

Марина Солнцева и Денис Есаков, основатели и кураторы коллектива de_colonialanguage, согласились поделиться со мной историей своей масштабной арт-инициативы Open Air Museum of Decoloniality, которая на много месяцев превратила главную площадь Берлина в свободный музей:

«Первая акция, которую мы сделали здесь, называлась “Who the fuck is Александр?”. Мы повесили баннеры «who is Александр the fuck?» в разных частях <площади> и стали опрашивать людей: “Вы знаете, кто такой Александр?” Мы ожидали, что будут вспоминать каких-нибудь немецких Александров, например Александра фон Гумбольдта<...> – но люди почему-то чаще упоминали Александра Великого, Македонского. И никто не знал, что это <название> посвящено русскому царю.

У нас была идея: что площадь надо переименовать. Потому что очень странно в 2022 году, когда российский империализм просто на марше и ведет военную кампанию по приобретению новых земель, видеть тут, в центре Европы, площадь, одну из самых гигантских площадей, которая всё еще носит имя российского империализма. Александр I был суперуспешным колонизатором: за время своего правления он присоединил огромное количество земель в Центральной Азии и в Восточной Европе. Это странно, да? Как минимум для нас это звучало как приглашение, и Александерплац выглядела как хорошее место, где можно развивать критическую теорию.»

Формат музея тоже был выбран неслучайно:

«Во-первых, это было смешно – назвать площадь музеем, для нас это был прикол – поиграть в музей… Тогда мы взялись за критику институций, институционализма, <создав свой> музей вот так вот, на площади, и начав делать там что хотим.

А во-вторых, сейчас существует деколониальная критика музея. Мы стали думать: что такое, например, музей без стен или музей, где делают события. Если мы регулярно делаем маленькие акции, то самым главным становится время, потому что если регулярно что-то делаешь, то ты уже превращаешь себя в устойчивую институцию, даже если в ней нету стен. Таким образом, мы пытались критиковать концепт музея и с этой точки зрения.»

Марина и Денис признаются, что не сразу пришли к интерактивному, вовлекающему формату своего «музея», а постепенно нащупывали подход к взаимодействию с площадью и ее гостями:

«... Мы заметили такую разницу, когда перешли из <закрытого> пространства в открытое пространство. В пространстве галереи существуют неписаные коды white cube. Ты знаешь, что ничего трогать нельзя, но если пришла на открытие, то, наверное, где-то еще алкоголя нальют. Все эти правила ты знаешь, они витают в воздухе, ты как бы знаешь сode of сonduct, как себя вести в white cube, какой бы он ни был. А на площади этого кода нет.

Сначала было такое: вот мы арт-коллектив, мы сейчас повесим работу. А потом мы достаточно быстро пришли к открытому формату toolbox, или gamefield, и с тех пор никогда не делали работу сами – делаем только набор инструментов и материалов, разворачиваем его на площади, и люди сами присоединяются к дискуссии. То есть мы задаем некоторую тему: например, “Кто такие Другие в обществе?”. Вот мы сделали баннер: “who is the Other” – и дальше у нас поле и бумага, маркеры, которыми ты можешь выразить свое ощущение, кто такие другие или какое твое было ощущение, когда ты почувствовала себя другой. И люди очень легко с этим соединяются, потому что чаще всего это очень открытый и доступный вопрос, не очень изощренный, всегда апеллирующий к какому-то персональному, личному опыту.

Очень прикольный момент был на одной из первых наших акций, которая была еще в 2023 году. Мы ее назвали Other Names, то есть отталкивались от идеи того, что площадь надо переименовывать. И мы решили сделать паблик ресерч: принесли розовую клейкую ленту, на которой стали писать имена феминисток со всего мира. Это были и чикано-феминистки из Мексики, и black american feminists, и из России, и из Центральной Азии, и из Восточной Европы, и африканские. Мы посмотрели, где, когда, что они делали, какие есть феминистические имена и стали их писать на этой ленте. Мы начали прямо с метро, потому что это был конец ноября, уже было темно и очень холодно. Мы расстелили ленту, заняв часть прохода. На нас немножко ругались <охранники BVG>, но мы обозначили себя как artists, и они как бы смирились. А потом мы эту ленту разрезали на отдельные имена и вышли <на Александерплац>. Тут есть вентиляционная шахта, металлический блестящий “тотемный столб” четырех метров высотой. Мы стали его обклеивать этими именами. К нам присоединились женщины, которые прочитали имена, тут же поняли, кто эти люди, сказали “Ой, давайте мы вам будем помогать!” и стали тоже обклеивать столб. И он был насколько ты дотягиваешься ростом – получается, в два с небольшим метра – обклеен полностью этими розовыми именами, стал розовый, и эта работа продержалась на столбе полгода.

Если ты предлагаешь toolbox, то люди тут же входят в этот обмен, и поле становится очень щедрое. Получается, финальная работа всегда создана безумным количеством людей на Александрплац. Это больше 100 рук, которые присоединились, что-то контрибутировали, что-то сделали, и получилось объёмное, разностороннее высказывание.»

Несмотря на то, что возможности для искусства в последние годы сжимаются из-за урезания городского бюджета Берлина, художники находят новые способы быть услышанными: музей под открытым небом – один из них. Марина и Денис уверены, что возвращение к прекарности в какой-то мере можете быть мотивирующим фактором: художники уходят в андеграунд и начинают творить по-настоящему независимый арт. Обратная сторона этой тенденции – необходимость поиска взаимодействия с властями и полицией. У ребят неоднозначный опыт в этой сфере: с одной стороны, Берлин всё ещё позиционирует себя как культурную столицу, потому полиция снисходительно относится даже к несогласованным акциям, если они не носят откровенно политический характер. С другой, происходит явная коммерциализация общественных пространств, чему Александерплац – яркий пример: не проходит и нескольких недель, чтобы на площади не организовывали какую-то ярмарку, показ мод или другой народный” праздник. Небоскрёбы, строгая регуляция разрешённых видов деятельности, коммерческий стрит-арт, не предполагающий никакого сотворчества, лишают общественное пространство его прямой функции – как места сбора простых горожан.

А их здесь немало: во время арт-акций ребята выстроили связи со всеми завсегдатаями Александерплац и, к своему удивлению, обнаружили, что туристы не главная ее составляющая.

«Вот в этих домах <панельки за Александерплац> живет большое польское комьюнити, и, соответственно, здесь очень много польских подростков, людей из польской диаспоры. Вот там, под мостом и вокруг вокзала, живет очень много бездомных, которые тоже пользуются этим местом. Летом они моются в фонтане, здесь всегда можно найти какую-то еду, попросить мелочь у людей. Бездомные очень часто и очень щедро делятся своими историями, невероятно страшными. Здесь много религиозных людей, свидетелей Иеговы например. Они буквально каждый раз к нам приходят с проповедями, благословениями, и они тоже очень активно, но при этом довольно односторонне участвуют в разговоре…

Здесь всегда пролегают повседневные маршруты местных жителей. Вот академики тут часто ходят и <видя наши работы> подмечают, что это может пересекаться как-то с их полем научных исследований. На Александерплац очень разнообразная аудитория, на самом деле.»

Всего с сентября 2023 по сентябрь 2024 года de_colonialanguage провели тринадцать акций. В 2025 году – ещё шесть перфомансов, объединённых названием Voices Otherwise и при участии пяти приглашённых художниц из Чувашии, Армении, с Северного Кавказа, Татарстана и Казахстана. В 2026-м коллектив собирается продолжить свои интервенции:

«Весной-летом мы будем делать Political Wardrobe. Мы разработаем шаблоны, притащим материалы: разные ткани, бумагу, из которых можно делать одежду. И центральная идея акции – что эта одежда должна выражать политические предпочтения, интересы, постулаты. Можно будет что-то написать, можно в цветах флагов сделать наряд или создать какую-то форму, которая считывается как что-то, что отображает твои политические <взгляды>... То есть мы изучим, как мода может быть политической, и планируем провести как минимум три таких Political Wardrobes. Всё это здесь, на Александерплац. А по итогам акции у нас будет дефиле.»

На вопрос, может ли искусство все еще быть сильным политическим высказыванием в наше время, Марина и Денис отвечают однозначно:

«Искусство всегда политическое – возможно, и не бывает неполитического искусства, потому что всё, что включено в нашу жизнь, уже имеет какое-то такое политическое значение. А сейчас, кажется, особенно.

Когда общественное пространство сжимается, тебе нужно находить новые места, где ты встречаешься с другими людьми и где случаются какие-то очень важные разговоры. То есть даже акт совместной готовки может стать политическим.»

Идею устроить такую акцию – коллективной кухни посреди центральной площади Берлина – de_colonialanguage тоже рассматривают как продолжение своего доказавшего успешность проекта Museum of Decoloniality.

Подробнее о прошлых и будущих акциях коллектива можно узнать по ссылке: https://www.instagram.com/de_colonialanguage/ -

Russian translation provided by Tatiana Bulanova