Art is the creation, the process, and the end result of human ingenuity. It is both the creative restraint paired with the liberty of an artist’s inner workings, the reflection of the personal self and the collective influence of others. Quite fascinating that art is and can be both timeless and yet the product of a particular time and era; an aesthetically pleasing conduit for understanding the history of culture. The circumstances in which these works of art may have been created under, and the reasons they were made can give us glimpses of the life of the creators. The ideas that shaped their understanding of the world, the expertise and craftsmanship that shines through, even down to the particular materials available to them - all on display for us to view, through the lens of artistry. Even people who feel otherwise about the historical aspect of art and/or are unfamiliar with [classical] art beyond surface level recognition acknowledge the value of preserving the legacies of those that came before us and those in the present.

As Alexandra Bardon, author of the article “Why is Art History Important? 12 Key Lessons” notes, “art history offers us far more than a collection of "greatest hits" or objects of market value; it provides a panoramic view of humanity itself, a timeline textured with the very fibers of human experience” (Bardon). As human experience is uniquely tied to individual perceptions of reality, art therefore provides visually striking interpretations of both the mundane and the extraordinary. That creations of artists are born from the accumulated experiences, knowledge, inspiration, and emotions only the artist is privy to. The collective effort to preserve the ideals of their time. Moments within their lifetime that can never be relived again. People or concepts may die with the passing of time, but through art and the various creations of artists, their legacy remains– long after their death.

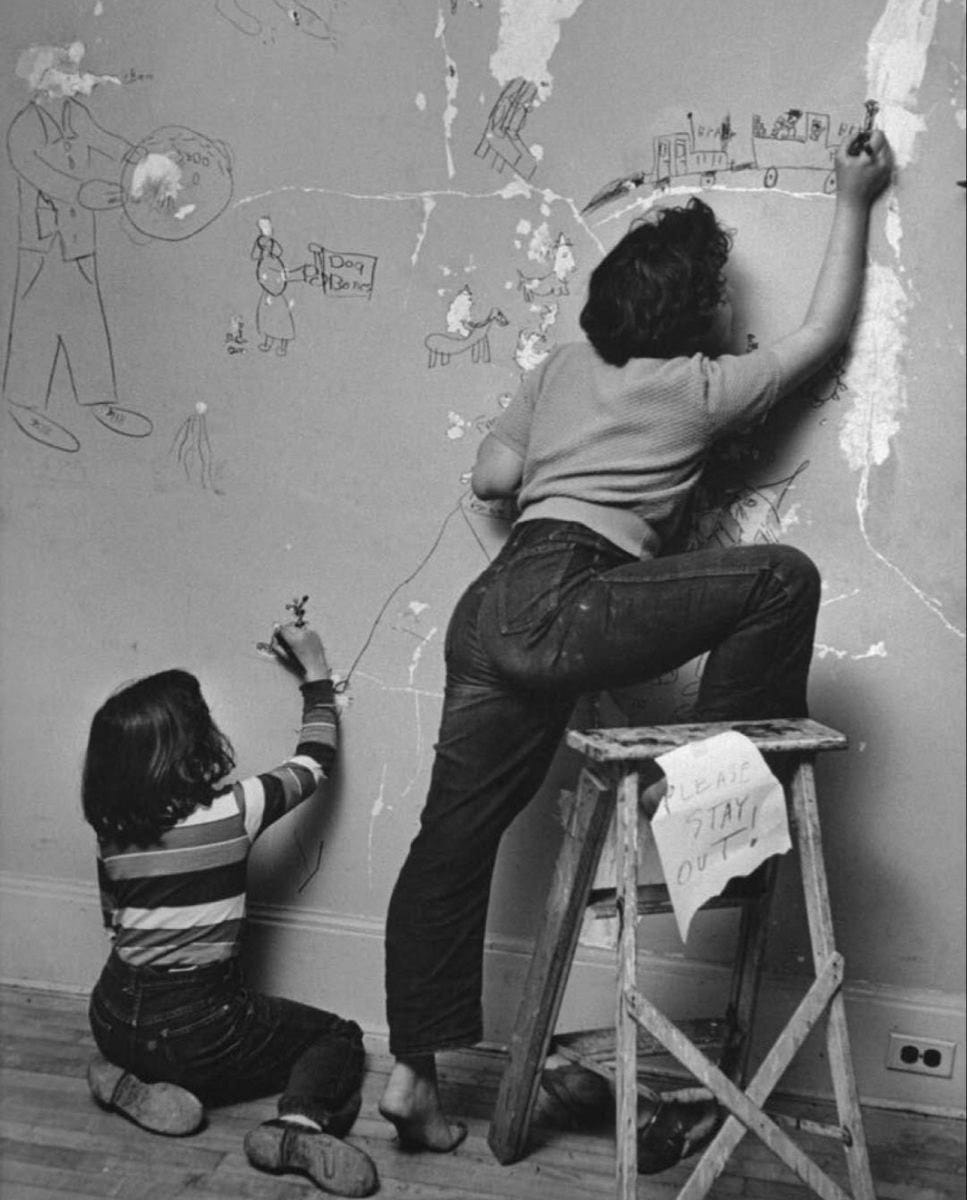

Ultimately, those inherent, intangible qualities are what gives art value that is difficult to define. Especially within the modern cultural climate, predominantly driven by hyper-consumption, for value is determined by what we feel the artist should deserve, and not does. And while that in and of itself is a major issue, the manner in which society nowadays consumes art and its treatment towards the art community, I also think about the disconnect between interest in the finalized result and interest in the process of creation. Because only when we can take a step back and focus on the big picture is when we can recognize art for what it is - the ultimate act of self-truth. To quote Bardon, “In essence, art history is not just about the past; it’s about bridging time, illuminating connections, and fostering a greater understanding of our shared humanity,” the key words being shared humanity. The reason I want to highlight this is because society is all too eager to bastardize the connections we have with each other. There is a cynicism to participating in art that societies from centuries ago would faint from scandalized shock. Yes, we can acknowledge that generous patronage allowed the artists to focus solely on art, or that only people with privileged backgrounds could participate in the creation and discussion revolving around art. We can acknowledge the failure to encourage accessibility to the wider public, specifically women, in championing artistic diversity.

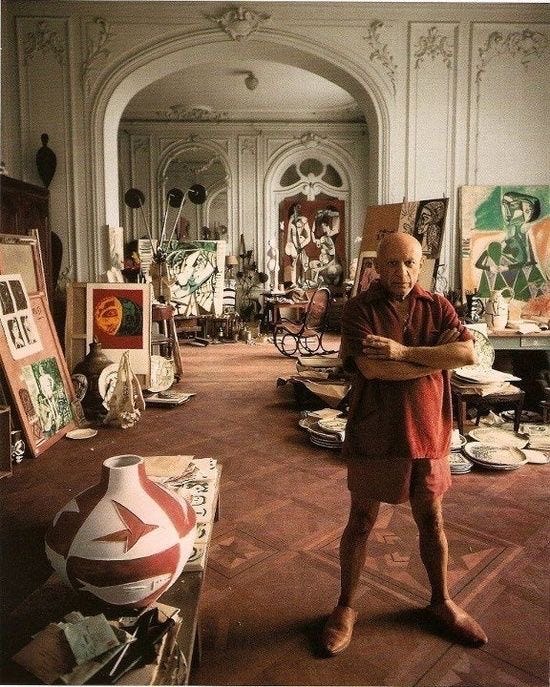

All of those things and many more faults (there are many artists, like Picasso, who are notoriously questionable people outside their public identities) can be true. And yet, despite these glaring flaws, art back then wasn’t treated the way society does now - an insignificant afterthought. Art back then was a celebration of science, math, philosophy, religion, and creative innovation, so to speak. But more importantly it was the celebration of community. As much as I have my gripes regarding Christianity, I believed artists like Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael created works that, in spaces specifically designed for communal worship, helped to enhance the religious experience. To have people from a variety of backgrounds come together under the same roof adorned with art that, for lack of better words, encapsulated the beauty that is religion. That this is a safe space to express yourself at your most vulnerable, allowing others the privilege of peering into the essence of you and vice versa. Art does that really well in that aspect, revealing the humanity in people and the ideals they strive for. People are humans first before White, Black, Male, Female, straight or somewhere on the queer scale, whatever differences society holds against who. And while the aforementioned artists’ art did have an agenda to push (the Renaissance was all about the positive progression of man), there is still a level of reverence and respect for the arts [and optimism for mankind] that nowadays are reserved only for those society deems as valuable contributors. In other words, those very same artists that are, unfortunately, already dead because they’ve become household names or those exploited under harsh working environments in order to produce recognizable art marketable for easy profit (see the anime industry).

Furthermore, as art is often a reflection of an artist’s self-truth (their identity), if not made palatable to society’s narrow-minded tastes or interests, society deems them not worth entertaining. The commodification of art further exacerbates this issue - mass production, overly simplistic, dumbified design priorities, the rising costs of living, artificial community bonding (social media frenzy), contribute to the devaluation of art both as a medium of communication and a quality of life. More than anything else, I suppose, art is deeply personal, and that scares many people because “...we're not just observing colors, shapes, and forms; we're diving deep into a narrative – a tale that speaks of traditions, beliefs, societal norms, and historical events. Each piece of art stands as a sentinel, guarding the stories of the civilization it stems from, allowing us to catch a glimpse of its cultural soul” (Bardon). I think people perceive classical art as this detached, professional piece of work, the gold standard that modern art fails to live up to and is subsequently scorned for because of the “woke agenda”. Especially given how accessible art, in its many forms, is to the general public, this form of self-expression can be seen as a threat to the comfortable status quo that conservative elitists have.

Art snobs decry contemporary art as a cultural offense against the all-time greats, scorn art styles that they deemed “nonsensical” (abstract/performative art) or “childish” (anime). Conservatives, on the other hand, take offense at the overt/covert messaging of art created by historically disenfranchised communities, claiming such politics have no place in a medium meant to appeal to everyone. These people want art to conform to topics that are “palatable”, “inoffensive,” and “mindful”. Yet, so much of the culture and discussions regarding art, however, has always been about creative innovation and challenging societal norms and conventional wisdom. It is a medium to speak volumes about personal stories, to bring to life feelings and emotions through expert use of concepts like color theory, light and shadow, and perspective when words cannot. A visual experience quite like nothing else, that only art can provide to better understand the world through. It is not just meant to look pretty. Art can disturb, reveal uncomfortable truths about societies or individuals many are unwilling to concede.

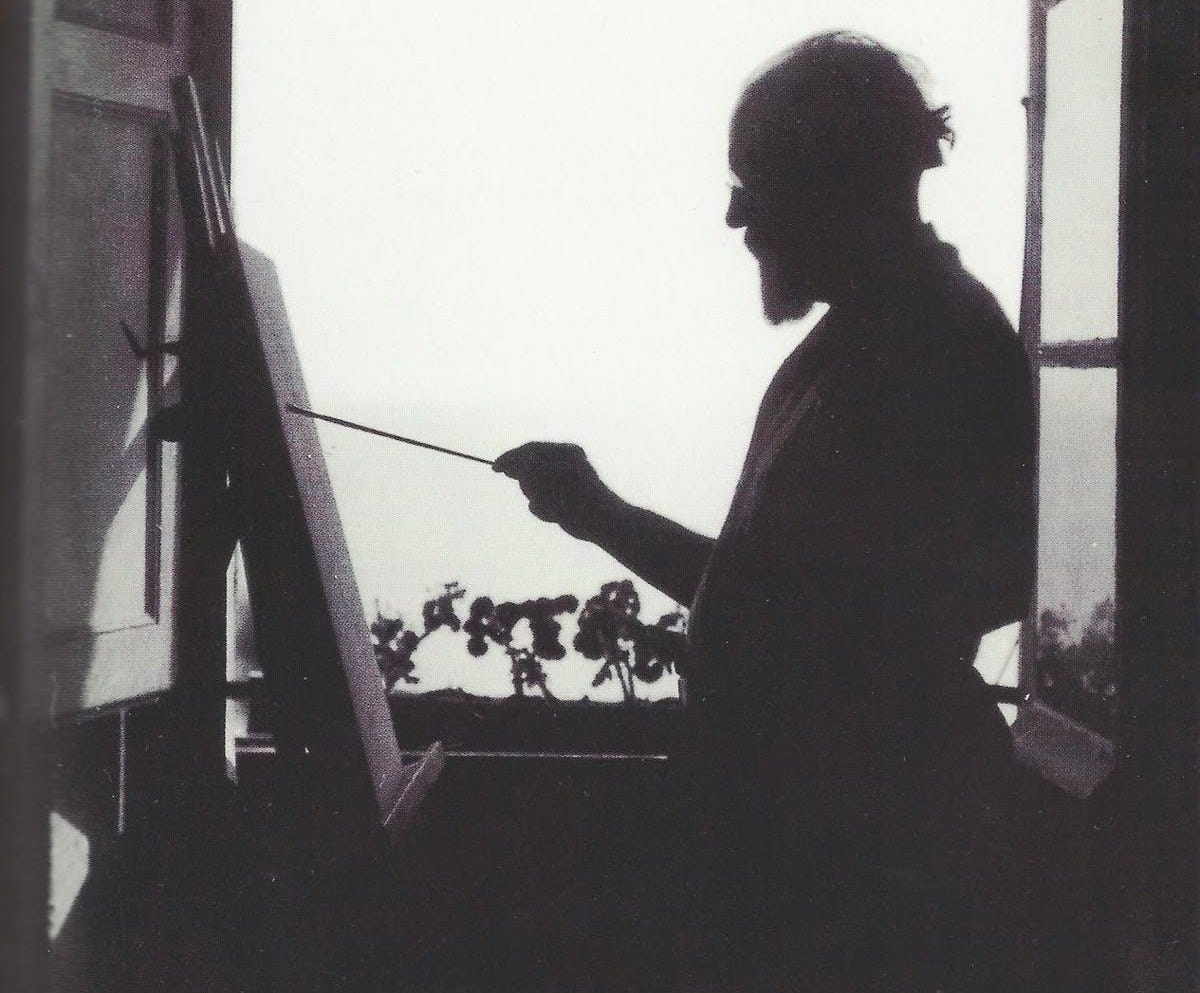

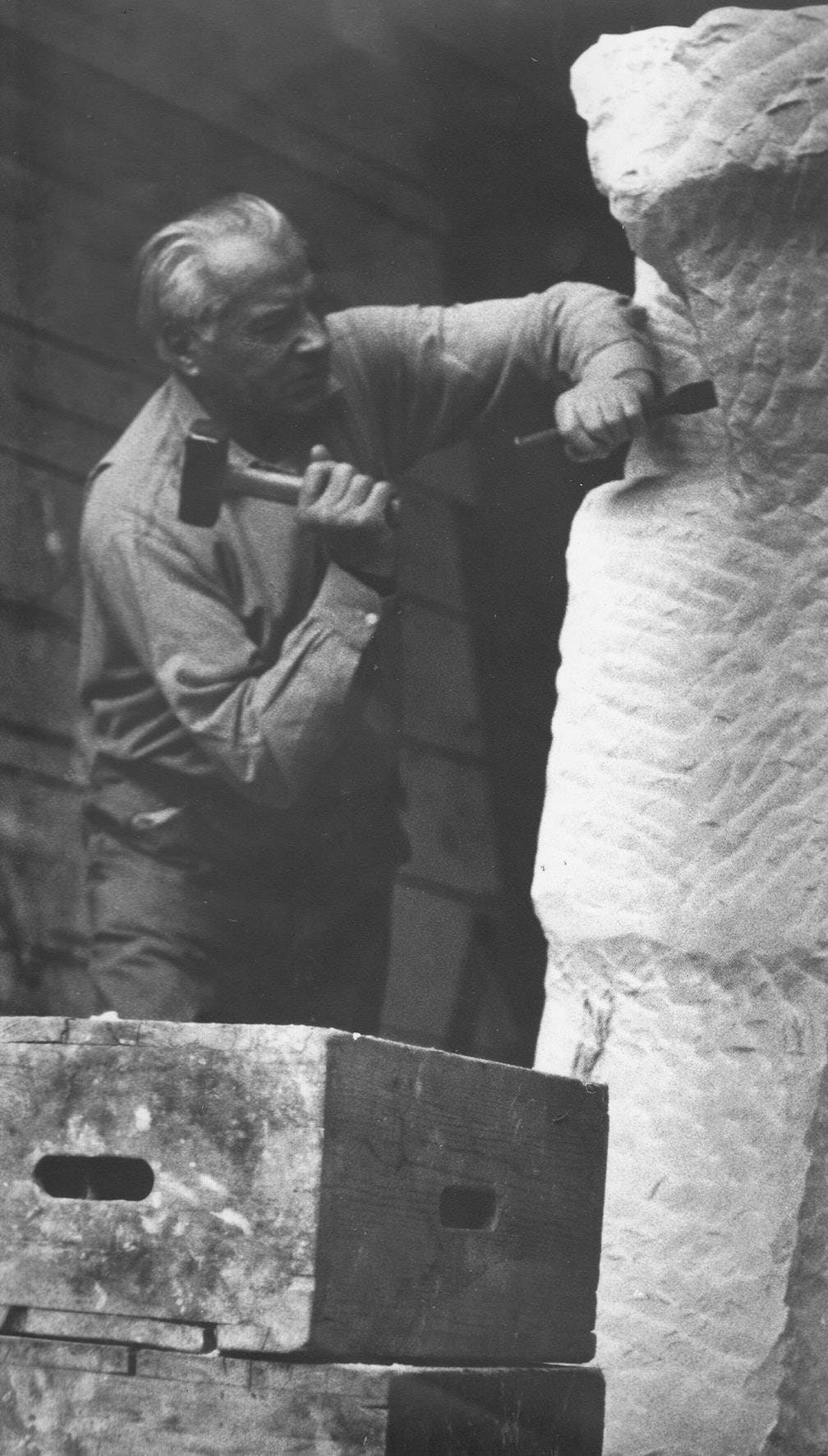

Art can raise awareness for social issues in a manner that oftentimes skirt past efforts by those in power to downplay through differing forms of censorship (i.e. banning of books, killing off journalists). For instance, one of the most famous examples of “political art” is Picasso’s anti-war oil painting “Guernica”, a direct response to the horrific Nazi and Fascist bombing of the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. Picasso himself described the bull as the embodiment of brutality and darkness (the decision to bomb innocent civilians), while the horse represented the suffering of the people of Guernica. Despite what contrarians might say about the way people perceive these works, creatives often create art with a specific intention or messaging in mind that can be hard to ignore. Especially if artists like Picasso publicly acknowledge the reason behind it; therefore, naysayers that don’t like or understand the messaging cannot just wave it off and claim that others are “seeing things that aren’t there” or “saying things that go against the artist’s vision”. Not when the content is as explicit as it gets, and especially not when said content is directly referencing said issues. Because art has always been political. Art has always been as polarizing and divisive as it is as universally beloved and respected. The truth of the matter is that understanding art is not just seeing and interpreting only the things you can see. It’s not just adding paint onto a canvas or shaping formless globs of clay into masterpieces. It’s just as much about the process as it is about the result. For art is about bringing to life and defining the things that make you you.