Going No Contact Is Not a Trend, It Is Survival.

Breaking cycles, choosing peace, and redefining family during the holidays

Christmas is supposed to be about family. About coming home. About warmth, forgiveness, and togetherness. Yet for many of us, the holidays come carrying grief instead of comfort and silence instead of celebration. This Christmas, I am learning that absence can also be an act of love, and that going no contact is not a rising trend, but a vital form of self protection and breaking the cycles of generational trauma.

Recently, I listened to Oprah Winfrey’s podcast episode exploring what she called “the rising trend of going no contact with your family.” While the conversation offered several thoughtful perspectives, I found myself unsettled. Not because the topic felt familiar, but because of how easily some of the participants reframed the pain of adult children into something palatable for public consumption, as a generational failure, a mental health buzzword, or worse, a lack of conflict resolution skills.

One Reddit user shared how deeply triggered they felt after watching the episode, overwhelmed by guilt. Guilt is the inheritance many of us receive when we choose distance. Social media has made it easier to find communities of chosen family, places where healing feels possible, but it has also amplified a troubling narrative, that parents are victims of abandonment and children are impulsively cutting ties.

What often goes unsaid is how frequently parents hide behind harmful claims that their children are “too sensitive,” “mentally unwell,” or “unable to communicate.” As someone who comes from a deeply complex cultural and traditional background, this dismissal feels painfully familiar.

My grandmother was a respected professor of psychology in Cuba, a fact I’ve long found both ironic and confusing, as mental health was neither valued nor protected in my household. When I began therapy in college to manage my CPTSD, my father laughed about it to a family friend, calling it “white people shit.” That moment did not shock me, it simply confirmed what I already knew. Healing to them was as foreign as they felt in this land. Survival was expected and seeking assistance was weak.

It took me years to begin letting go of my upbringing. Only recently did I understand why I loved Ella Enchanted so fiercely as a child. I am her. She is me. Bound by invisible rules, trained to endure quietly, and praised for obedience rather than authenticity.

Our home was often a refuge for others. My mother took in children who had nowhere else to go, escaping households far harsher than my own. I learned early how to care for others, housing friends against my family’s wishes, feeding them, giving impromptu “spa weekends” in my trailer home to distract them from their pain. I told myself that because I was helping others, my home couldn’t possibly be abusive. Someone else always had it worse, right?

I viewed people who cut off their families as Americanized, white-washed. How could anyone do something so ungrateful? My father foreshadowed this fear often, warning us that Americans abandon their parents, put them in nursing homes, forgetting where they came from, discarding those who gave them their entire lives. Did he know I would grow up to see? To ask questions? To want better? To want more?

I was made to feel ashamed for wanting more, accused of trying too hard to assimilate, to be like my American peers. I already looked like them, a fact often weaponized against me. So I doubled down. I clung tighter to culture, tradition, expectation. My family became my religion. Their sacrifices were my purpose. My dreams were not my own.

As I aged, cracks formed. My interest in psychology deepened. My eldest daughter role of fixing everyone intensified. What I saw as an attempt to regulate my nervous system and prevent destruction was perceived as control. I always knew where we were headed if nothing changed.

It took becoming a mother myself to finally draw a line.

Recently this year after another big spectacle that took me away from attending an event with my husband, I asked for one thing: therapy. A boundary. A chance to heal together .That request was met with resistance, anger, and repeated violations. I sought therapy for myself, to work on my own health and healing, and I was very clear, if they would not work on themselves, I could not maintain a relationship. They were used to me caving in. But, this time, I couldn’t. My body wouldn’t let me. My nervous system was breaking down. I was disappearing.

There is never one single reason a child goes no contact. As a hospice nurse in Winfrey’s podcast so accurately stated, it is “a thousand cuts that bled me dry.”

I had always been the family’s unofficial advocate, the child with a social justice complex, unafraid to name what was wrong. I was constantly defending my mother and sister, earning the nickname ‘abogada’. I had already gone low or no contact with a few relatives over what I felt was unforgivable behavior. When my request for therapy was denied from weeks to months, things escalated beyond anything I could have imagined.

My family became defensive, relentless. Over twenty phone numbers were used to harass me. Letters and social media posts were published about me to audiences that included former professors, peers, and community members. Despite repeated pleas from me, my husband, and my best friend to stop, because it was severely impacting my mental health and my ability to parent my high-needs child, it continued.

I still asked for therapy. It was still my only ask.

Now I live with hypervigilance. I had to get a new phone number because each new number began to trigger panic. I flinch when cars pass my house. I keep my curtains closed. They have shown up unannounced, banging on my door, leaving gifts that feel less like love and more like bargaining.

People who watched me grow up somehow forgot that I was once a child too. They took my mother’s Facebook rants as fact and scoffed at me when I greeted them kindly, as I always had.

A fact I never thought I would find myself writing is that I am not in contact with a single member of my incredibly large family.

I don’t know what the future holds. Going no contact is not easy, and I would argue it is far harder for the child who initiates it, despite what others may claim. I am no longer interested in valuing parents’ feelings over their children’s safety.

I don’t know if my family will ever come to terms with who they are or what they’ve done. I don’t know if they will forgive me.

What I do know is this, I am the intelligent woman they raised me to be. I am doing what is best for myself and my child. If they cannot accept that, then radical acceptance will have to carry me forward.

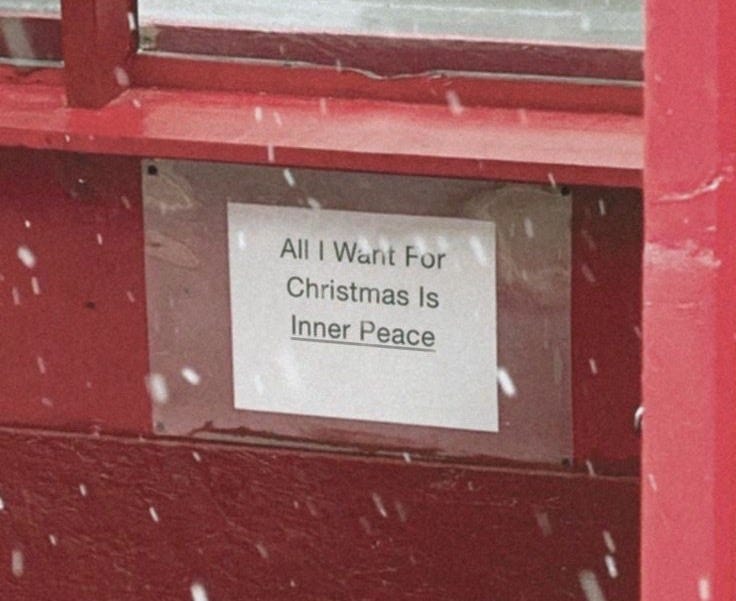

This Christmas, I am choosing my chosen family. I am creating new traditions. I am honoring the quiet, brave work of breaking cycles, even when it hurts.

Especially when it hurts.

I feel like sometimes parents forget their children are full people separate from themselves, people worthy of respect, and apologies. Forcing your adult child to interact with you when they’ve asked for space is not love, it’s selfish. When I established boundaries with my parents as an adult, I didn’t ask for therapy because my older sibling asked they same and they refused (thankfully they have since started to go), I asked to be treated like an adult, and I said I would not be yelled at under any circumstances. I understand my parents are also just people, people with trauma, hardship, and barriers they themselves are navigating, but your history does not give you excuse to treat others badly, it can contribute to your lack of toolset, but when made aware of how you’re harming others, you should respond with apologies and amends, yet so many respond defensively that they “tried their best” but sometimes, thats not good enough, and it’s your responsibility as a parent to make things right with your children you have harmed, even if you didn’t mean to.

I admire your strength and hard-won wisdom. Thank you for speaking truth to social power, and also for sharing in such a personal way. Wishing you AMAZING peace, and tons of hugs with your chosen family!!