Anonymous, Not Invisible

The Tea App, Systemic Harm, and the Real Conversation We Should Be Having

When news of the “Tea App” started circulating, a friend of mine texted me, saying she didn’t like the drama surrounding it. She described it as an app, once meant to keep women safe, now “abused” by women “trashing guys,” spinning tales out of bitterness and breakup fallout.

She meant well. She was speaking from her own experiences, from what she saw and was hearing and seeing online. But I couldn’t help but notice how quickly the conversation, like so many others, pivoted from the issue of systemic male violence to the possibility of women lying.

The truth is, we’ve all heard this before. We’ve all lived this before.

And I’m tired. We’re all so tired.

Let’s begin with the facts and numbers:

Over 90% of sexual abusers are male.

1 in 3 women will experience some form of sexual violence in her lifetime.

Most won’t report it. Of those who do, fewer than 2% of rapes in the U.S. result in a conviction.

And yet, the cultural needle keeps tilting toward “what if she’s lying?”

Never, “what if he’s done this before and will do it again?”

Never, “why does she need anonymity to feel even slightly safe speaking up?”

Safety Isn’t Slander

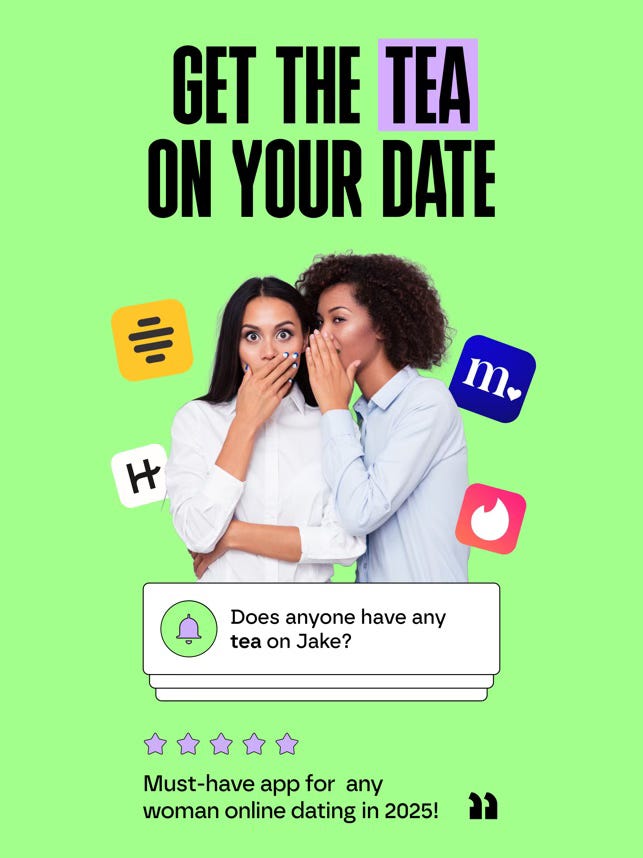

The Tea App, anonymous and primarily user-led, was created as a digital whisper network, a modern-day survival tool for women navigating dating and safety in a world that rarely protects us. But like all things built in a broken system, it was imperfect. Some posts may lack verification. Some users may be venting their emotional pain. But those flaws do not erase the very real purpose behind it, a lifeline for people who live under the constant threat of being assaulted, manipulated, stalked, or worse.

We need to hold space for two truths at once: Any tool, especially anonymous ones, can be misused.

And this app exists because the justice system has failed to protect us. Repeatedly. Historically.

The Tea App’s critics seem to fixate on the potential for abuse, but they rarely talk about what it means to be abused. Doxxing women on 4chan? That’s abuse. Leaking their identities and information for speaking out? That’s violence.

It reminds me of the Netflix documentary The Most Hated Man on the Internet, where Hunter Moore built a career off of humiliating women through revenge porn, aided and cheered on by other men. Moore and the many men who partook faced minimal consequences—until years later, after a mother mounted a campaign to take him down, and even then, the punishment was not enough and many went unpunished. Hunter Moore still to this day has shown zero remorse since this release and has openly critiqued the Netflix Documentary.

Meanwhile, the women behind the Tea App were doxxed immediately. Their safety was threatened in retaliation for trying to protect others. The double standard is glaring.

“Not All Men”—But Still, Most Violence

My friend reminded me, not all men are guilty. That some women are “bitter.” That false accusations exist.

Let’s unpack that.

Saying “not all men” might be true. But it’s also irrelevant. Because women don’t know which ones are safe, and it is also always, somehow a man.

The ones who laughed with us over dinner also cornered us at 2 a.m.

The ones who cried during breakups also stalked our Instagram stories for months.

The ones who seemed “nice” were often the most dangerous of all.

Women have learned to live with a constant internal radar, scanning for red flags, second-guessing gut instincts, texting friends when we get into Ubers, screenshotting messages just in case. That radar wasn’t paranoia. It was survival.

The Lie About “Lying Women”

The myth of the lying woman, bitter, vengeful, weaponizing her emotions, is an old and deeply misogynistic one. It’s been used for centuries to silence women. It’s the same myth that was used to burn women at the stake, to question rape victims on trial, to ask “but what was she wearing?”

Is it possible for someone to fabricate a story? Of course. Is it common? The data says no. Studies show that only between 2–10% of sexual assault reports are false—a rate comparable to any other crime. And those rare instances don’t erase the lived trauma of everyone else.

Focusing on the theoretical few who lie instead of the countless who suffer is a distraction tactic. It's a derailment. It’s not justice, it’s denial.

This Isn’t About Dating Frustration

Another point raised in my conversation: “Some women can’t handle rejection.”

But the stakes for men and women after rejection are not the same.

When women are rejected, we’re called “crazy,” “clingy,” “desperate.”

When men are rejected, too often we’re called “dead.”

Needle spiking. Drink tampering. Stalking. Femicide.

These are not random acts of violence. These are patterns. And we don’t need an app to tell us they exist. But sometimes, we do need an app to warn us about the next guy.

When the System Protects the Wrong People

This isn’t just theoretical for me. I’ve seen what it looks like when the system knows and does nothing.

In college, I was part of an organization that sometimes sent students out of state. We were trusted to be adults, no babysitting, no chaperoning. It was understood that we could handle ourselves.

One of the students on my team, later turned out to have been accused of sexual assault back in his hometown. High schoolers involved in one of our events Googled us and found the allegation online. That was the first time any of us heard about it.

Later, we found out that our advisors had known. They let him stay on the team. Let him travel across state lines with us. Let him drink with us. This was also the same person who used slurs and when I reported it to our advisor, nothing was done. In fact, a large percentage of the team defended him and everyone in general accepted him for who he was. I was made to feel “annoying” and like I was doing “too much”.

But this kind of negligence and complicity isn’t unique. Here’s another example:

A close friend of mine had a best friend growing up whose father was a gymnastics coach in the 1990s. One of his former students, whom he had been coaching since she was 9 years old, came forward to say that he had groomed and assaulted her for years, beginning when she was just 14. He was charged and pleaded guilty, and was only sentenced to 5 years probation. There are multiple New York Times articles about him.

And yet today, he lives freely. He’s wealthy, respected, and embraced by a new community.

My friend’s parents even knew about his past.

And still, they let their daughters stay overnight in his care.

This is why women whisper.

This is why we turn to anonymous tools.

This is why we build systems outside of “the system.”

Because time and time again, we watch predators go free, with their reputations intact, while survivors are told to stay quiet or be destroyed. Sexual assault is still so minimized in today’s society that prolific convicted predators are even allowed to become president.

So What Now?

Yes, the Tea App needs stronger guardrails. Yes, we should be vigilant against false accusations. But we should not throw away a tool for survival because it isn’t perfect. Not when the systems built to protect us never were.

My friend and I don’t see eye to eye on this, and maybe that’s okay.

But I’ll never stop defending a woman’s right to speak up, even anonymously, when the world makes it almost impossible to do so safely.

If the Tea App has done anything, it’s reminded us of the vast, unaddressed demand for community accountability in the face of a failing system. If we dismantle it, we must replace it with something better. Not just safer for men’s reputations, but safer for women’s lives.

Until then, we will keep whispering to each other.

We will keep warning each other.

We will keep surviving.

Even if it makes the internet, men, uncomfortable.

Sources

National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC)

https://www.nsvrc.org/

RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network)

https://rainn.org/

U.S. Department of Justice – Office for Victims of Crime

https://www.google.com/search?client=safari&rls=en&q=U.S.+Department+of+Justice+–+Office+for+Victims+of+Crime&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8&sei=AuGHaJntBYr_p84PtOGGuQs&dlnr=1

World Health Organization (WHO) – Violence Against Women Reports

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS)

https://bjs.ojp.gov/

“False Allegations of Sexual Assault: An Analysis of Ten Years of Reported Cases” – Violence Against Women Journal

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1077801210387747

The New York Times – Coverage on sexual abuse trials and institutional complicity

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/12/05/us/harvey-weinstein-complicity.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/11/us/politics/sexual-assault-school.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/25/sports/larry-nassar-gymnastics-abuse.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/11/opinion/letters/colleges-sexual-assault.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/06/us/politics/sexual-harassment-weinstein-oreilly-metoo.html

The Most Hated Man on the Internet – Netflix Documentary

https://www.netflix.com/title/81387065

Women’s Media Center – Reports on media bias and survivor credibility

https://womensmediacenter.com/reports

UN Women – Global statistics on gender-based violence

https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/11/1157046

https://data.unwomen.org/global-database-on-violence-against-women

https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women

https://data.unwomen.org/global-database-on-violence-against-women/data-form

https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/research-and-data

https://forum.generationequality.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/GBV-AC-Progress-Report-2022.pdf

https://forum.generationequality.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/GBV-AC-Progress-Report-2022.pdf